Another British invasion will soon arrive on American shores: the New Theists. That’s the name for a growing number of public boosters for the Christian faith, who see it as part of a comprehensive plan to save Western Civilization. Our contributor Țara Isabella Burton is more than skeptical about this trend, and here she explains why.

— Santiago Ramos, executive editor

Some years ago, I dated somebody who matched with me on a dating app because I identified myself as someone to whom religion is important. He had specifically searched for someone to whom religion is important. Back then, I was a relatively-new Christian convert, and delighted to have found a partner who was not just willing but delighted to accompany me to church — still unfamiliar to me — and to spend brunch afterwards dissecting the sermon. Church was the focal point of our brief shared life: the basis of the folie a deux inevitably fostered by romantic passion.

I don’t remember at what point he revealed that he was not, in fact, a Christian. His desire for a religious girlfriend, he told me, was based on an intuition that the sort of woman who took her faith seriously was the sort of woman who would make a good wife. More broadly, he’d found in the social practice of Christianity the necessary building blocks of a truth-based life. He also believed, in a vague, Jungian way, that Christianity was correct when it came to fundamental metaphorical truths (the triumph, say, of the Logos) regardless of the dubiousness of its literal mythological points of dogma. To live in a Christian way, which is to say, to live within the orthodox structures of institutional Christianity, particularly when it came to marriage and child-rearing, for him meant to live in opposition to secular modernity, to the oversexualization of society, and to the “social justice warriors” evangelizing feminist liberation and promiscuity. More charitably, perhaps, it meant the affirmation of something true, good and maybe even beautiful over and against the muck of relativism, and the painful nihilism, of his college-era Richard Dawkins-style atheism. He’d been a rationalist, once, and maintained a rationalist’s commitment to the pragmatic: Christianity might or might not be true, but as a social technology, it worked. He cited Jordan Peterson’s work on Christianity — and its usefulness in the field of self-help — as an inspiration.

We did not, as it happens, get married. I don’t know the current state of his soul. But I think often about his approach to Christianity. What struck me back then as a personal idiosyncrasy has, in the past decade, become a defining trait among members of the broader anti-woke coalition. Christianity-as-counterculture, as a vibes-based phenomenon, has taken hold (and by now, already peaked) among the self-consciously transgressive dissident Right. But it has also taken hold, in a less explicitly aestheticized form, among the broadly-conceived tech-Right: a demystified parallel to, if not a dark mirror of, various forms of “trad” Christianity proliferating on the online Right.

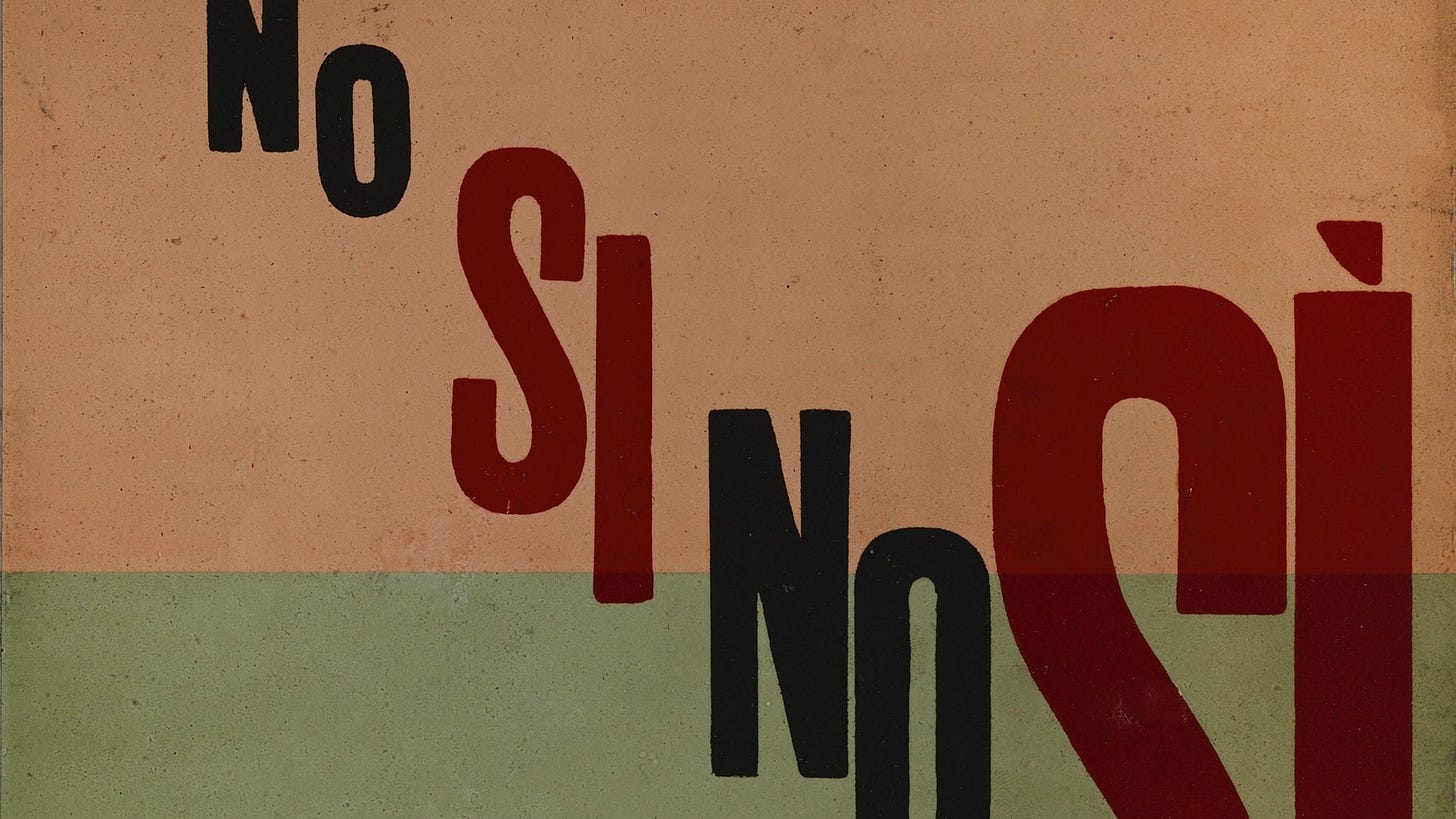

In this view, Christianity is good, useful, and desirable both because its fundamental metaphorical message says something true about human nature, and also because a society in which people broadly hold to that metaphorical message is preferable to the nihilistic carnival of postliberal modernity. Also in this view, to be a Christian is to defend Western civilization, Western culture, tradition, gender norms, linguistic nominalism, truth as a virtue, the inherent meaningful language, the begetting of children, and the life lessons taught to us by Jesus and the Old Testament prophets alike. It’s also to defend the proliferation of Christian ideas as a necessary part of social improvement. Call it memetic Christianity.

Memetic Christianity holds, correctly, that human beings have a natural need for religion, perhaps even for God. It holds correctly, too, that the kind of religious “remixing” found among the spiritual but not religious, in which anyone can essentially create their own religion that “works for them,” can offer little for individuals or society as a whole.

We find this memetic Christianity, for example, in the writings of Ayaan Hirsi Ali, who in a Christmas 2023 article for UnHerd “came out” as a Christian, having publicly left Islam for atheism nearly twenty years earlier. Hirsi Ali wrote that her reason for becoming a Christian was, in part, is “global.” “Western Civilization,” Ali writes, “is under threat” from Communism, from Islamism, and from “the viral spread of woke ideology.” Christianity, for Ali, not only fills the “God-shaped hole” but also does what the “rules-based liberal international order” cannot: provide a unifying memetic force for a society emboldened to resist these external threats. Christianity is synonymous with the “legacy of the Judeo-Christian tradition,” which Ali defines as an “elaborate set of ideas and institutions designed to safeguard human life, freedom, and dignity,” established defenses of “the market, of conscience, of the press.” So too does Christianity offer Ali “spiritual solace” — although she is silent on her relationship to its more specific and scandalous doctrines. For Ali, Christianity is a “tool,” a “unifying story,” a set of ideas preferable to “videos on Tiktok” when it comes to winning the “heart and minds of Muslims.”

That’s not to say that Ali doesn’t believe in Christianity — or, at least, that she finds in the Christian story a fulfillment of her spiritual hunger. In an interview with UnHerd, Ali describes an encounter with a therapist during a period of deep depression. “I explained to her why I didn’t believe in God, more than that, why I actually hated God, and then she asked me to design my own God and she said ‘If you had the power to ... make your own God what would you do,’ and as I was going on I thought, yeah, right, that’s actually a description of Jesus Christ. ... And so instead of inventing yet another new god, I started diving into that story.”

Ali’s story is a compelling one, in part because it represents the power of memetic Christianity at its most complex. Ali has deep spiritual pain, and a deep spiritual yearning, and, in the process of attempting to fill that yearning, she realizes that Christianity makes sense, as a story that can tie together disparate theological and social and psychological elements of her experience of the world. It would be churlish to deny that this sense-making — Christianity as a theory through which to meaningfully understand the cosmos — is separate from the Christianity of faith. I generally consider myself someone who believes in those more scandalous doctrines — the Resurrection, say, or the virgin birth — and yet I know that when my own faith sometimes falters, it is Christianity’s capacious sense-making that pulls me back from the brink of doubt.

But when Christianity as meme comes to replace Christianity as truth, we find ourselves in dangerous theological territory. Or, to put another way, if Christianity weren’t true (or we didn’t, at minimum, truly believe it to be true), ought we to affirm Christianity as a necessary noble lie for a more orderly, or just, or optimistic society? And — if it is merely a noble lie — what’s the point of optimism at all?

We find this vision of memetic Christianity as a social good, in the work of the Paypal and Palantir founder Peter Thiel, who has spoken publicly, if vaguely, about his commitment to the religion. Speaking at an event in San Francisco, Thiel characterized Christianity as, in essence, an avenue away from the kind of mimetic imitation described by his onetime mentor, the philosopher René Girard, towards originality and innovation. “The Christian intuition,” he said, “is always that we should be on the side of transformation and not just taking the world as it is.” Thiel describes transhumanism, from a Christian perspective, as something that “doesn't go far enough” because it fails to transform the soul alongside the body. (Compare this with the remarks of another event attendee, who stressed: “Jesus loves you ... that is the good news of Christ.”)

Elsewhere, in a perhaps-unorthodox essay for First Things, Thiel presents the Judeo-Christian tradition as the only means by which technological world-improving change can take place: a centuries-long vision of order over the deep: “Judeo-Western optimism,” Thiel writes, “differs from the atheist optimism of the Enlightenment in the extreme degree to which it believes that the forces of chaos and nature can and will be mastered. … Science and technology are natural allies to this Judeo-Western optimism, especially if we remain open to an eschatological frame in which God works through us in building the kingdom of heaven today, here on Earth — in which the kingdom of heaven is both a future reality and something partially achievable in the present.”

So too Peterson — vague about his own religious convictions — has returned to Biblical themes of transformation with his most recent book, We Who Wrestle with God, a commentary on the book of Genesis. Genesis, Peterson writes, offers a “brilliant and inspiring vision,” namely “the idea that the god of all gods is attention and the creative, transformative word — the Word that transforms monstrous possibility and darkness into the world itself.” The rightful leader of this Word-based metaphysics, Peterson writes, is not the richest or the strongest or the most Machiavellian, but the “attentive, visionary communicator: the person who watches most closely and tells the best story, past, present, and future.” And the force behind it, Peterson tells us, is “not the immature, hedonistic whim of the moment” but rather “something higher. Something that genuinely brings together, establishes names, places, and renews; something upward striving and reflective of the truth.”

There is something to each of these visions of Christianity: something that I cannot deny was integral to my own conversion. I too came back to Christianity, in part, out of disillusionment with Tinder and with Tarot cards; I too felt, in the pull of high liturgy and the smell of incense in my hair, something at once numinous and concrete. And it is true, too, that there is a long, rich and vital philosophical tradition of understanding the implications of the Word that was there in the beginning, the Word made flesh, as a predication not just of our personal relationship with God but of the interconnected structure of the entire cosmos. And the most charitable interpretation of Ali, Thiel and Peterson is that, when you are a public intellectual in a world where it remains cringe to speak of, say, Jesus’s love, it is far easier to talk about the memetic importance of the God-man as an abstraction than it is to talk about this one particular man who was born and died and rose again. I make no claims about anyone’s internal faith. And yet, the celebration of memetic Christianity in wider trad and tech circles alike — as useful religious technology — does, often, focus on Christianity’s political and ideological potential at the expense of, well, Christ.

Memetic Christianity chills me both within and beyond the cultural war in which its proponents see it as a necessary weapon. It is the same chill I get when I think about their ostensible rivals: the Remixers of the post-relativism age. It is not merely the notion that a useful, if false (or at least inconclusive) idea, if spread among an intellectually acquiescent populace (by, necessarily, a knowing elite), might be an efficient mechanism of social order. It is, even more worryingly, a religiously-tinged affirmation of the bleakest tenets of our post-truth age: that the memetic and the metaphorical are realer than, and prior to, the particular or the literally true. Jesus Christ becomes, in this rendering, merely a paradigmatic rendering of the God-man: the human being who, through knowledge, through will, through innovation, through the creative power of the (so-called) Western intellectual tradition, succeeds in transhumanist self-divinization. If Christianity is not literally true, in other words, it becomes instead a kind of Hermetic magical transhumanism, in which Jesus is a mere metaphor for the divine in all of us. Storytelling, command of language through logos, becomes in this vision the ultimate human prerogative: the creation of reality through the judicious dissemination of memes. Man is a divine reality-creator because he is a self-determining storyteller. (It’s telling that both Thiel and Peterson’s accounts of the Judeo-Christian tradition center a figure that seems a lot more like a contemporary technological innovator than a Nazarene carpenter).

Memetic Christianity, in other words, succeeds in combatting the excesses of what it sees as “woke” ideology: the “cultural Marxism” that (in its proponents’ view) demands a complete dismantling of social institutions. (One would do well to remember, here, that the Biblical Jesus had little compunctions about the dismantling of conventional institutions — he was perfectly willing, for example, to overturn moneylenders’ tables in the Temple, despite it being an established social practice). But it does so by giving up the heart of its own doctrine: the emphasis on particularity, on a Jesus that is not abstract or hypothetical but rather a literal incarnation of God in physical space and historical time. What we are left with, rather, is not an antidote to the “religion of modernity” but rather the religion of modernity itself: the divinization of the self, and its ability to shape and reshape reality in the image of its own will. It is a worship of culture qua culture, of civilization qua civilization, of man as creator, as tool-maker, and memes the most powerful tool of all.

I do not know what I would do, or think, if I did not believe in the literal truth of Christianity. Intellectually-speaking, memetic Christianity, with a dose of well-managed, private Nietzschean hedonism might well be the most sensible philosophical framework on which to build a lasting society, to preserve the dignity of the human person, and provide sufficient psychological solace for people’s “God-shaped hole.” And there are times, when my own faith wavers, that the affirmation of faith — the decision to believe even when I struggle to believe; the belief that it is right and good to believe in this, sustains me in times of doubt. But to treat Christianity as merely a useful memetic force to resist modern decline is only to hasten it: to preach a gospel predicated on a Word synonymous not with divine creative reality but human fictive speculation. To turn the ten commandments into Twelve Simple Rules is to cede what Christianity has, and Remixed religion doesn’t: the chance that it might be actually true.

If it’s not, after all, then what’s the point? If we are to reduce Christianity to the status of noble lie or useful meme, if we are to decide that those of us clever or educated enough to see the tragic, nihilistic truth of human meaninglessness ought, thanks to something between the call for social cohesion and a no-longer-justifiable sense of vestigial moral urgency, to affirm something untrue, then why not take this logic to its ultimate conclusion? Human culture — human language, human story, human creativity — exists to be shaped by the memetically-powerful, and to shape the sheeple in turn. There are two kinds of people in the world: creative magicians, and those foolish enough to succumb to their superior’s ideas. Only the strong — not warriors, in this disembodied age of ours, but rather storytellers — can have, or claim, authority. It’s a consistent set of dogmas, to be sure. But it isn’t Christianity.

Wisdom of Crowds is a platform challenging premises and understanding first principles on politics and culture. Join us!

I appreciate this very much -- the effort to make Jesus Trump's cultural attache have seriously pissed me off. He doesn't work for any political project, and it's not like he didn't have the option. (When Peter cut that centurion's ear off, one part of him *had* to be thinking, "Hey, maybe *now* he'll lead us against the Romans!") I talk about the political implications that I think my faith has, but I try to keep the "Christian" before the "leftist" in "Christian leftist." The second thing is only a satellite to the first thing.

I think if I were just picking a religion off a menu for utilitarian reasons, I might be tempted to go with the somewhat Americanized progressive Islam that some of my brighter first-year students believe in. Or perhaps one of the friendlier varieties of Wicca. I don't think I've ever met a mean witch. But asking other people to believe something that you yourself think is bullshit, just for the sake of social cohesion, is insulting to others. Anyway, I think Jesus is God, so here I stand.

For instrumental reasons, I returned to Church with my family last year after decades away. It was an act of faith without belief. I subscribe to the idea that belief is largely a gift or a grace from God. I keep faith that God may bestow such a gift to me, but in the meantime, attendance has been good for my family and my community. I am jealous of those who can argue from a position of faith against instrumental reasons to identify with Christianity. Aligning one's convictions with one's behavior is an incredible act of faith for some. I welcome those choosing Christianity for instrumental reasons. I think that is how it has probably always been. I think Ryan Burge made the point that once the social expectations for church attendance eroded, those who didn't necessarily believe were given cover to stop attending. The number of believers didn't change; the number of those sitting in the pews did. For my money, I'd rather have pews full of those with mixed motives than quarter-full ones filled with true believers. God can make of us all what he will.