Happy holidays, Crowd! We’re pleased to be publishing an essay by our brilliant friend Ian Tuttle, who also happens to be a research fellow at Aspen’s Philosophy & Society program, as the Tuesday Note on the culmination of Advent. We hope you have a wonderful and restful holiday break with your loved ones.

— The Editors.

One of the disorienting parts of living in the twenty-first century is that the twentieth has yet to end.

In his 2010 book, The Burnout Society (published in English in 2015), the philosopher Byung-Chul Han attempts to diagnose the distinction between our present and what came before. “Every age has its signature afflictions,” and ours, he contends, are “depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), borderline personality disorder (BPD), and burnout syndrome.” We live in a “neuronal” age.

At the source of these pathologies is what Han calls an “excess of positivity.” We encounter very little in the way of alterity, or genuine Otherness, he suggests. Instead, we find that very little challenges our sense of identity; it is readily assimilable, easily absorbed into the Same. We face very little in the way of exterior constraints. We are “free” — so free that, having nothing to constrain it except itself, “the ego overheats.” This is what we diagnose as “burnout.” Depression, similarly, is a function of finding nothing that is distinct from myself, nothing that draws me out of myself.

Writes Han, putting a fine point on it:

Depression—which often culminates in burnout—follows from overexcited, overdriven, excessive self-reference that has assumed destructive traits. . . . [The depressive subject] is tired, exhausted by itself, and at war with itself. Entirely incapable of stepping outward, of standing outside itself, of relying on the Other, on the world, it locks its jaws on itself; paradoxically, this leads the self to hollow and empty out. It wears out in a rat race it runs against itself.

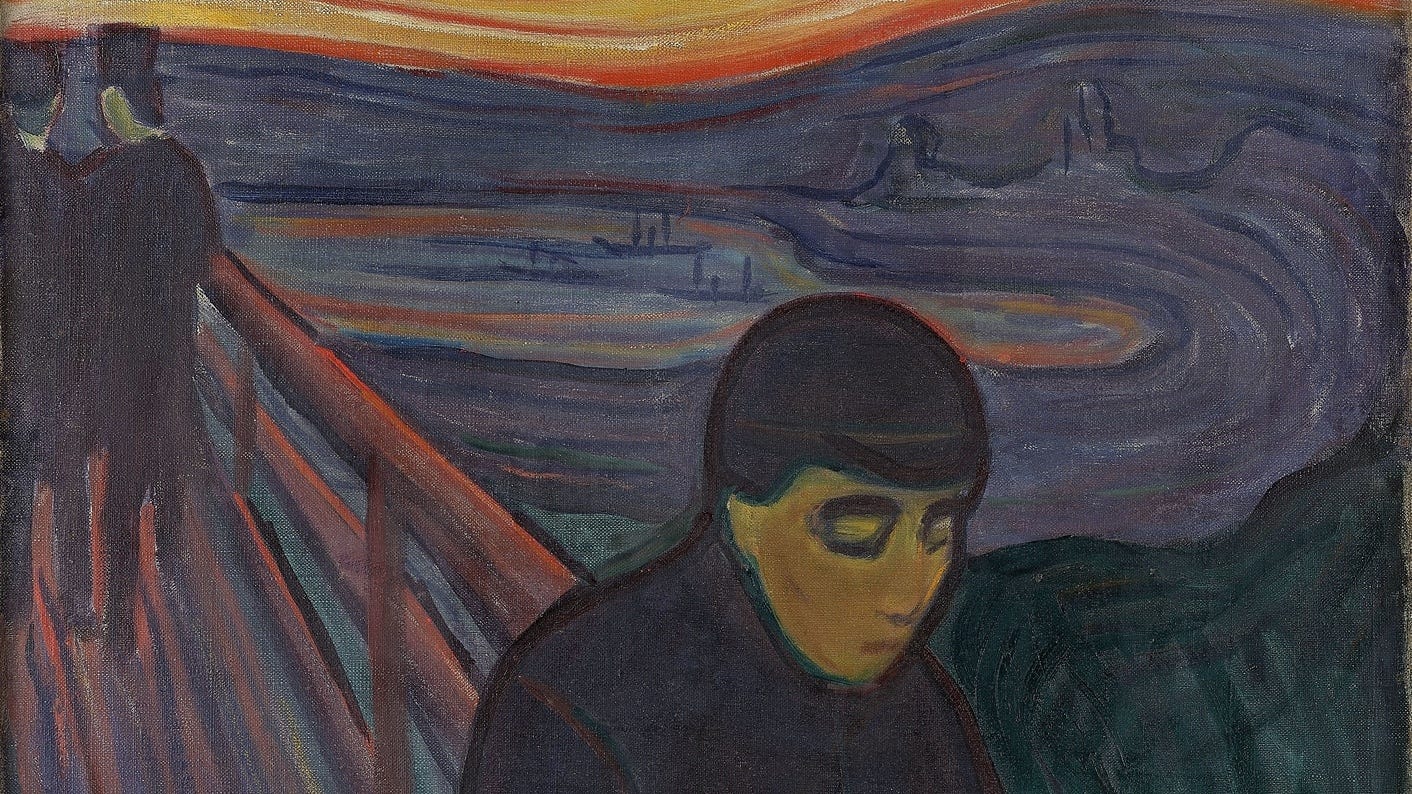

The opposite of depression is, perhaps, what the Greeks called thaumazein, “wonder”: astonishment at what is not, finally, me.

But that becomes harder and harder to come by, especially as the mirror of digital technology reflects us back to ourselves more perfectly. No wonder that more than 18 percent of American adults, or some 47 million, are currently undergoing treatment for depression — up from just over 10 percent in 2015.

Han draws a contrast between our excessively positive age and the previous, Cold War-era world, which he characterizes as an “immunological age.” “The immunologically organized world,” he writes, “is marked by borders, transitions, thresholds, fences, ditches, and walls that prevent universal change and exchange.” The immunological age is characterized by attack and defense. The “disciplinary society” theorized by figures such as Michel Foucault was concomitant with the immunological age. Where there is negativity — that is, threatening Otherness from which we must protect ourselves — we are likely to find vigorous defensive measures: border guards, aggressive public-health bureaucracies, nuclear weapons.

One way to think of the postwar world is as a program dedicated to overturning the immunological age. The reduction of barriers to the flow of goods, in the form of unrestricted trade; capital, in the form of international investment; people, in the form of mass migration; and ideas, in the form of digital communications technologies, was an effort to eliminate genuine, and therefore potentially threatening, alterity, by reducing all to the same. (Think of homogeneous non-places such as the shopping mall, the airport, the McDonald’s.)

Yet when Han writes that “today, even the so-called immigrant is not an immunological Other, not a foreigner in the strong sense, who poses a real danger or of whom one is afraid,” something seems to have gone awry.

The immunological paradigm surely persists. Certain forms of nationalism, populism, and post-liberal thought have strong immunological elements, as does the behavior of certain governments. The current administration’s approach to immigration enforcement is one example. So is its decision to strike boats allegedly ferrying drugs to American shores.

The immunological paradigm has legs abroad, too. Hungary and Poland have reintroduced border checks, pushing back on the European Union’s migration policies. Ukraine has been forced to repulse a Russian assault. Covid was a literal, worldwide immunological event, which had the additional effect of shifting relations between major powers (the U.S. and China, especially) toward greater antagonism.

So, compare Roberto Esposito and the opening of his 2002 book, Immunitas:

The news headlines on any given day in recent years, perhaps even on the same page, are likely to report a series of apparently unrelated events. What do phenomena such as the battle against a new resurgence of an epidemic, opposition to an extradition request for a foreign head of state accused of violating human rights, the strengthening of barriers in the fight against illegal immigration, and strategies for neutralizing the latest computer virus have in common? Nothing, as long as they are interpreted within their separate domains of medicine, law, social politics, and information technology. Things change, though, when news stories of this kind are read using the same interpretive category, one that is distinguished specifically by its capacity to cut across these distinct discourses, ushering them onto the same horizon of meaning. This category . . . is immunization. . . . [I]n spite of their lexical diversity, all these events call on a protective response in the face of a risk.

The extraordinary confusion of our time might be characterized this way: we have pathological symptoms in abundance, but they point in different, even competing, directions. Are we suffering from an excess of positivity — cf. the relentlessly solicitous reply of the LLM: “That’s a smart question!” — or an excess of negativity — cf. rising antisemitism? Are we struggling with too little Otherness — cf. “deaths of despair” — or too much of it — cf. crimes or acts of terrorism committed by migrants? Which is it?

Our discontent yields bizarre spectacles. Negativity and positivity each generate specific forms of violence. Oversensitive immunological responses perpetrate outward-directed violence: militarism, sectarianism, racial and ethnic hatred. Oversensitive neuronal responses generate inward-directed violence: hyperactivity, exhaustion, self-harm. Like crossing waves, these phenomena are creating strange patterns of interference: the televised ICE raid that doubles as entertainment; the mass shooting that is also an elaborate form of suicide. This much, at least, is clear: the patient is critical, divided body, mind, and soul.

Is any therapy available to us? Han seems to offer a suggestion that he does not explore. The world of too much positivity he refers to as “a terror of immanence,” a terror “immanent in the system itself.” The world of too much negativity, by contrast, is best figured by Medusa, who “stands for radical difference that one cannot behold without perishing in the process.” That is, on one hand, violent immanence; on the other, violent otherness.

Yet Han’s logic — and his invocation — suggests the possibility of an Other who is, also, not other; something outside ourselves that also restores us to ourselves; something that transcends us and yet embraces us. Neither Other nor Same, neither negative nor positive, is enough, but only their reconciliation — an impossible union of spheres.

We might consider the possibility that the extraordinary confusions of our time will not — cannot — be solved from within our time. We might consider the possibility that the remedy for our broken world will require a different kind of physician.

Wisdom of Crowds is a platform challenging premises and understanding first principles on politics and culture. Join us!

Thanks for this essay. I do wonder if we are simply too torn as people. It reminds me of the jam jar theory- give yourself 3 types of Jam and you can find your favourite easily and are satisfied. If you are given 20 then you lose the ability to be satisfied and find your favourite. Perhaps, too much choice in our lives, both personal and professional, undermines the ability for us to feel satisfaction.

There is also perhaps a natural temptation to blame other things for our own perceived failures. Just as drunkenness, idleness, and affairs were the downfall and cause of misery for many a person in the past, perhaps today, we leap into diagnoses and rely on them akin to comfort blankets. There is still something very visceral about staring outwardly into the abyss with little but ourselves in the background.

My recent short story https://nimnim1.substack.com/p/poly-hell