Gemma Mason is a writer from New Zealand who previously appeared on Wisdom of Crowds with a powerful and unconventional personal essay about religious belief, superstition and love. Today, she is back with reflections on pacifism, justice and how American violence looks like from outside its borders.

— Santiago Ramos

My husband looked at me this morning and said, “Welp, thank you very much for marrying me.” He meant, thank you for being the reason that I am here and not there. Spring is starting in New Zealand. Is the American fall beginning, in more ways than one?

My own distance from American shores feels less to me like a relief and more like a fact to be mindful of. I have lived in America, I am married to an American, and like much of the wider world I spend perhaps too much time staring at America’s political twists and turns. Still, it would be foolish of me not to acknowledge the distance.

I was talking to one of the old ladies at my Quaker meeting, a while back, about how political polarization seems so much stronger in the USA than it is here. She said, yes, she always used to remark about that with an American friend of hers.

It’s the internet, I suggested, and she laughed.

“Oh, no, dear,” she said. “This was in the 1970s!”

Well, I thought. That’s told me!

Her name is Linley, by the way. She believes that there is that of God in everyone, by which she really does mean traditional God. After Donald Trump was elected for a second time she told us all to stop moping and go out there and improve the world. Once I suggested, to an old man in Christchurch who spoke bluntly about his own death, that she was a welcome source of calm perspective. He looked at me like I had suggested that a tiger was a cozy pet to snuggle with.

Linley’s belief about “that of God in everyone” sounds similar to the idea of all people being made in the image of God, but it’s a very specific mindset with its own implications. The phrasing is from a famous exhortation by George Fox to “be patterns, be examples in all countries, places, islands, nations, wherever you come, that your carriage and life may preach among all sorts of people, and to them; then you will come to walk cheerfully over the world, answering that of God in every one.”

Quakers believe, essentially, that everybody already hears moral truth in their heart. The voice may be small, and without being attended to and developed it may not amount to much, but it’s there. Your job is not to put the right feeling into people but to answer what they already have, and perhaps to learn from what they know that you have not yet considered. It’s a controversial proposition; it’s also a powerful way to behave. I don’t know if it’s true, but I find myself thinking that it is the sort of thing I could take on faith. As another Quaker friend once told me, it’s an idea that can feel worth holding on to because it is hard to believe sometimes.

I am, strictly speaking, an “attender” and not a “member” of my Quaker meeting. Most of the time this barely matters, but I think about it a lot. I worry that I am not enough of a pacifist to officially join. I have been inspired by pacifists in many ways, throughout my life, but I don’t see how it can ever really work, as a general rule. There are some situations where it seems like disarmament is just allowing yourself to be harmed with impunity. It’s easy to be for “peace” in the abstract. Peace in practice is more complicated. Calling myself a pacifist because I support the former would just be cheap.

Mary Dyer’s pacifism has been on my mind, lately, courtesy of an internet commenter who tried to convince me that women’s freedoms will always be dependent on the men who fight for them. Freedom was, in his view, the product of force and only force. I wonder.

Mary Dyer was born a Massachusetts Puritan in 1611. She was driven out of her community for heresy, went to England, and became a Quaker. When she returned to Massachusetts, she was imprisoned and then banished, on pain of death, for her religious views. She defied that banishment multiple times, and was eventually sentenced to death by hanging in 1660.

Mary Dyer went to the gallows with her head held high, hand in hand with the two men convicted alongside her. Dyer’s execution, and her defiance in the face of it, became a touchstone for persuasion, both of the Puritans who witnessed her death and the authorities back in England who made a succession of decrees ordering greater religious freedom over the subsequent decades.

If Mary Dyer, and others like her, had not been willing to die for the cause of living alongside other people with different beliefs, would there be a United States of America? Could a Puritan colony like Massachusetts and a Quaker colony like Pennsylvania and all their many different neighbors have come together into a single nation, if the citizens of one were subject to execution in another? Surely not.

Mary Dyer and her fellow martyrs helped make the United States, and part of why that happened is that they took persecution with defiance but without retaliation. It’s a complex move. The Quaker belief in religious freedom was not just about freedom for themselves but about freedom for everybody. They believed in persuasion. They were willing to persuade with their lives.

It all looks so clear, when you tell the story like that. But maybe some of that historical clarity is an illusion that is dependent on a specific narrative about violence and death. Mary Dyer could have just accepted her banishment. She believed in religious freedom, but at the time not everyone did. I’m sure there were people who thought that she got what she deserved.

Charlie Kirk died a martyr of sorts, shot in the throat while attempting to persuade. Unlike Mary Dyer, it may be that his martyrdom comes to stand, not for freedom and dialogue, but for the dark moral clarity of a movement that may now believe with all its heart that free speech is a lie, that persuasion and principles have been dead in America for a long time now, and all that is left is fighting over the remains. One way or another, violence has a narrative force that is hard to resist.

John Woolman would have liked to be a martyr like Mary Dyer. The Quaker history that he had been taught growing up had specific ideas about what heroism ought to consist of, and frequently it consisted of dying for your beliefs. But Woolman was born in 1720, and there were no longer any places nearby for him to prove his convictions by being executed for religious freedom.

Woolman had to content himself with other causes. Abolitionism was not yet an official Quaker position, and some of his neighbors still kept people in slavery. Woolman set out to persuade them. He wrote earnest pamphlets, examining the motives that might lead an otherwise good person to continue enslaving people. He thought carefully about the broader virtues that would be needed to make a society without exploitation. He refused, visibly, even to profit from slavery by proxy, wearing linen rather than cotton and eschewing dyes such as indigo, which were produced by slave labor. A modern boycott is an exercise of consumer power; Woolman’s search for purity was more like a willing sacrifice for the sake of principle.

Woolman also allowed his convictions to lead him into dialogue with people he disagreed with. Some of his most moving stories of persuasion are incredibly intimate and interpersonal, as when he was called to write the will of a neighbor who had been recently injured:

I considered the pain and distress he was in, and knew not how it would end; so I wrote his will, save only that part concerning his slave, and carrying it to his bedside, read it to him; and then told him, in a friendly way, that I could not write any instruments by which my fellow-creatures were made slaves, without bringing trouble on my own mind: I let him know that I charged nothing for what I had done; and desired to be excused from doing the other part in the way he proposed: We then had a serious conference on the subject; at length he agreeing to set her free, I finished his will.

Did Woolman win? Slavery was eventually abolished, though Woolman didn’t live to see that happen even amongst Quakers, let alone in the wider United States that didn’t yet exist when he died. And slavery was abolished in violence and war — a war in which Woolman himself would certainly never have fought, devout pacifist as he was.

Pacifism can offer false moral clarity if you don’t think hard enough about it. Eschewing violence does not just risk martyrdom. It risks passivity, even complicity. The standard Quaker response to this is to continue to seek other actions besides violence that are possible and meaningful.

Pacifism at its best turns away from the shiny narrative power of violence, its justifications and its allure, and looks for something better beyond the conflict. It is said that liberty is bought with the blood of patriots, and sometimes it is, but liberty is invented by the peacemakers, scrabbling techniques out of the dirt for ways to live together without killing each other.

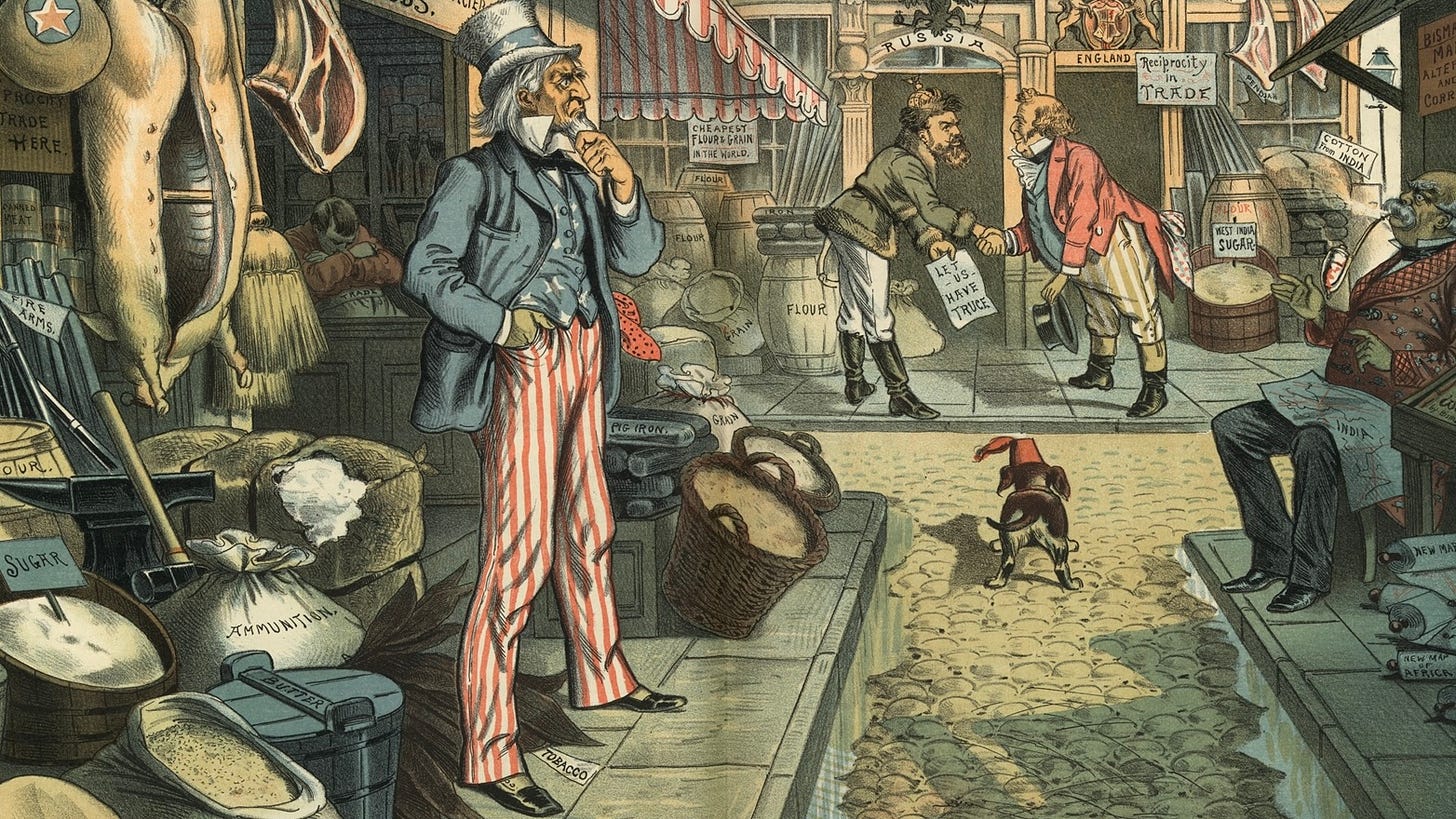

One thing I keep realizing, as I watch Americans wrangling over the future of their country, is that there is a sense in which principled liberals are pacifists, in practice, even when they would never call themselves pacifists by conviction. Like pacifism, liberalism is committed to persuasion as an alternative to violence. Like pacifism, liberalism is difficult in practice, risking complicity at every turn. And this is not surprising, because liberalism was at least partly created by pacifists.

The part-time pacifists with dirt under their fingernails are worth a lot. As existing systems of liberalism fracture, can new ways of peace and liberty be invented? If it’s useless right now to kill for liberty, and you’re unlikely to die for liberty, then how do you live for liberty? By what acts of courage or generosity will you shape a future you’ll never see in a country that might be changed from the one you have? You can’t know in what ways this is a long defeat and in what ways your actions will create new hope as the years go by.

You cannot put the good into people, or societies, or countries, but you can try to grow whatever good may already be there. I know that there is a lot of good in America yet. I have faith that, no matter what, some good will remain.

Wisdom of Crowds is a platform challenging premises and understanding first principles on politics and culture. Join us!

Great piece Gemma!

Anyone who says Charlie Kirk was a Martyr isn't using the same definition for Martyr as the historic church.

I'm not a Quaker, but I try to be a pacifist. (I'm also not totally bought in on Total Depravity so maybe I'm more in agreement with Quakers than I realized.) The anecdotes of Dyer and Woolman were striking in their moral clarity. And while I do think freedom of speech is the lynchpin of any multi-religious liberalism. I have stopped making 'American' my main identifier when I engage in the public square. Nation-states are inherently violent. My hope isn't that America gets better. Although I do wish for that. My expectation is that divine intervention is the only thing that can rescue us from ourselves.

"Jesus, come quickly."