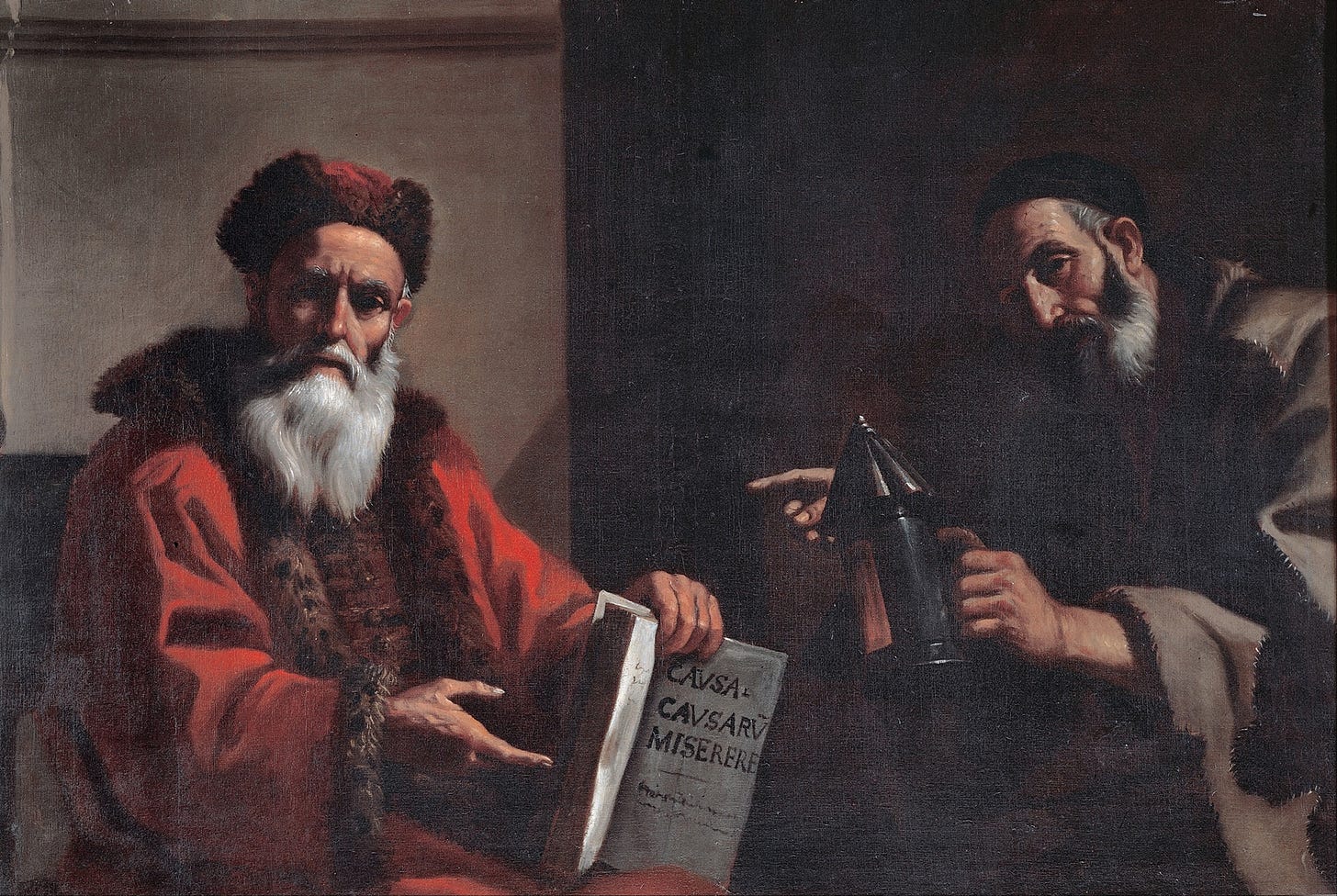

Commitment to democracy usually means a pugnacious rejection of anything that smells even distantly “aristocratic.” But this commitment often involves a hidden admiration for what is not, strictly speaking, “of the people”. Modern democratic polities retain a faith in expert ability to rescue them from multivariable problems; embarrassingly, we also ret…

Substack is the home for great culture