Oscar nominations are announced today. Don’t bother, says playwright and WoC contributor, Matthew Gasda: the movies suck. Even the middlebrow stuff has become stale. We live in the era of the “wikipic.”

— Santiago Ramos, executive editor

“Disneyland is presented as imaginary in order to make us believe that the rest is real.”

American films don’t feel like films. It’s a hard thing to describe — but we all know it; or those of us who remember what movies were like at least ten years ago do. The same way that cars are all the same colors, new apartment buildings all look the same, or young peoples’ faces share the same look (Gen Z has a look), movies all seem to take place in the same narrow, smushed range of color, performance and style. And it’s not an accident: I’ve been told more than once by Hollywood executives that they rely on viewer data. There is an international AirBNB style, and there is a national film style.

Modern American prestige movies are part of the evolutionary chain of what Dwight McDonald once called “Midcult”: “the formula, the built-in reaction, the lack of any standard except popularity [covered] with a cultural fig leaf.” Supposedly serious contemporary cinema feels gamed, optimized; Oscar-contenders all share certain “quality” markers: desaturated color palette, handheld intimacy, tasteful scoring. They are just as thoroughly mechanical as Marvel movies, but are designed to evade triggering variants of Martin Scorsese’s 2019 critique of Marvel movies (that comic book movies are “theme parks,” not films). If anything, Scorsese’s criticism of Marvel was a straw man. Scorsese’s own prestige fare for Netflix like The Irishman and Killers of the Flower Moon — while they still reflect Scorsese’s genius — have an industrial quality to them. The Scorsese Cinematic Universe today stands perilously close to becoming a Midcult theme park.

The rise of the digital platform has meant surveilling the audience; digital platforms don’t just stream content, they also study their viewers, converting each watch session into “valuable” behavioral data; market research is continuous and invisible. While money has flooded into the TV and film industries from Amazon, Apple, and other non-traditional players, there hasn’t been a corresponding boost in quality — actually the opposite. Amazon, Netflix, and Apple et al. have transformed the industry for the worse. Flows of capital have created a new cinematic vocabulary (whether on streaming or megaplex movies) that standardizes and reinforces practices for production designers, cinematographers, screenwriters, art directors, directors, actors, and editors.

Even if a director’s or writer’s intentions are to do something beyond creating Netflix goop (and I imagine most movie people start out at least with the idea of doing something greater), there’s now a locked-in expectation and technical foundation for polished, hyper-detailed, ultra-perfect sets and shooting styles. Modern tastes are so powerful, fixed, inflexible and uninteresting that the aesthetics of Instagram — gym-sculpted physiques, muted color grading, and smooth digital overlays — have become film aesthetics in general. Moreover, actors now favor naturalism and internalism, erasing any hint of theatricality or heightened gesture. These are sometimes necessary, by the way, to break the illusion that the past — particularly in costume dramas, which are extremely popular right now — is indistinguishable from the present.

The illusion that the past is just like the present dominates the spate of what might be called the “Wikipics”: biopics that feel generated from the most obvious, surface-level material. The most salient and popular recent example is James Mangold’s Dylan Wikipic, A Complete Unknown. (Mangold basically seeded the genre with the parodied Walk the Line in 2005.) Like other recent Wikipics Blonde, Elvis, Bob Marley: One Love and the miniseries The Offer, A Complete Unknown reflects Hollywood's obsession with manufacturing simulacra of cultural touchstones. In a few years, AI programs like Sora will be able to make movies like this in an hour.

These wikipics compress real figures into exhausting sequences of recognizable moments and predictable dialogue. SNL 1975, also released this fall, epitomizes this approach; the straight-from-Wiki protagonists don’t so much live their roles as narrate exposition (“90 minutes of live television … by a group of total unknowns!!”). Rachel Sennott speaks with an anachronistic vocal fry, almost in a taunt, but it doesn’t matter because the dialogue (as with the rest of these films) exists to underscore the historical significance we already know. All of these wikipics could have been titled, “A Known Quantity.”

In wikipics, actors are cast not for their ability to capture the essence of their subjects, but for their capacity to provide a recognizable facsimile (a broad impression that can be marketed in trailers and recut on TikTok). The films are constructed like greatest-hits compilations: here’s Elvis meeting Colonel Parker, here’s Marilyn posing over the subway grate, here’s Dylan going electric. It’s cinema as cultural taxidermy — preserving the skin and fur while removing all traces of the genuine vitality that made these artists and moments significant (and surprising) in the first place.

In A Complete Unknown, for instance, Greenwich Village feels lifeless, reduced to a Pinterest board version of history; 1960s Greenwich Village isn’t rendered as the vibrant, colorful space we see in period photography and video. Instead, it becomes a dull, sepia-toned imitation, like a Quince sweater catalog. It makes the Village feel like it’s populated by Gen Z extras in thrift-store costumes.

Period pieces don’t have to feel this way. Jack Fisk, Terence Malick’s set designer for The Tree of Life, went to extraordinary lengths to reconstruct 1950s Waco, Texas, but the film’s power isn’t in that meticulous historical reconstruction. It’s in how the performances and cinematography create a specific emotional structure; it’s the way Malick makes his modern actors live in another world (and you could say the same about his period piece The New World).

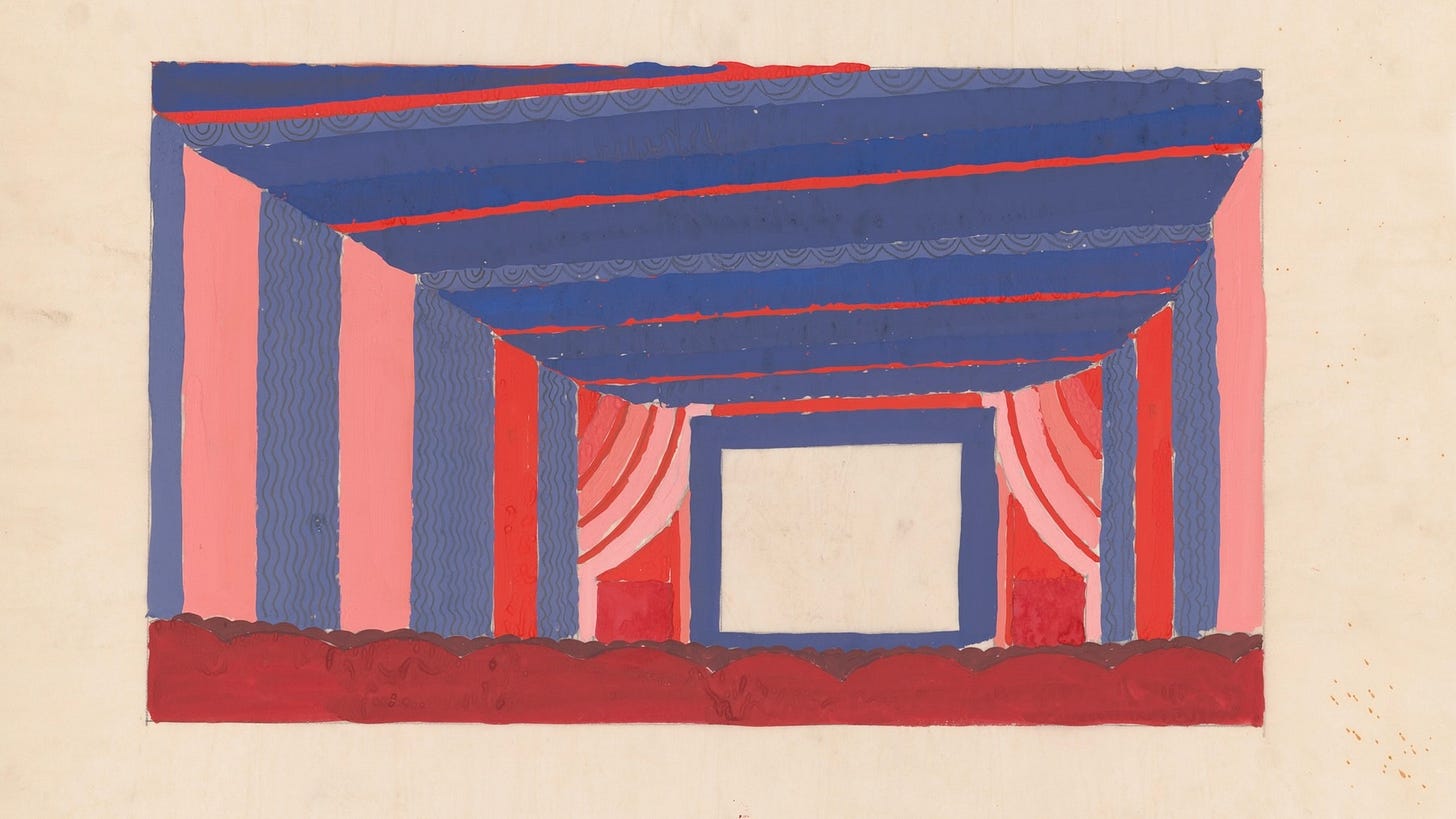

Or consider Fellini’s Satyricon. While absurd and fantastical, it conveys a profound sense of the ancient world — it is truly alien, almost like science fiction. Fellini made a tremendous leap of intuition with Satyricon. His grotesque, polychromatic, insane Rome captured the spirit of Petronius rather than slavishly adhering to historical accuracy.

In James Ivory’s A Room with a View, the flawless reconstruction of Edwardian England works because the performances never feel strained or self-conscious. Ivory not only reconstructed the past; he brought to life the wit, aestheticism and vigor — the lost world of pre-war Britain.

Barry Lyndon, similarly, creates its own complete cinematic reality. Through Kubrick's precise compositions, natural lighting, and deliberately artificial performances, the film doesn't just show us the 18th century; it constructs an aesthetic space that follows its own internal logic. When we watch Barry Lyndon, we’re not seeing actors pretending to be in the past, but rather inhabiting a world that exists solely within the film’s carefully constructed parameters.

By contrast, A Complete Unknown is nothing — not past, not present, not future … Not a movie. It is a series of well-assembled moving images, but you can see the stitching. You can practically hear the voices of the agents and producers who got Timmy Chalamet in the picture. You can tell it’s synthetic–polyester, not cotton.

With A Complete Unknown — as with so many movies and TV shows of the past 10–15 years — we can feel the entire machinery of filmmaking straining to fabricate and simulate authenticity. The film lacks an essential self. No cinematic ontology is ever established. Instead, it offers famous — or soon-to-be-famous —people in historical drag, romanticizing the past while simultaneously infecting it with the blandness of the present. What we get instead is an aesthetic dead end. The hyper-optimized design logic of 2020s cinema dominates the film, robbing it of the relief from contemporary aesthetic monotony that audiences might seek.

The thesis of the film seems to be: if Timmy broods into the camera long enough, we’ll understand something about the character of genius. It’s not so easy. The movie is terrified of mystery, surprise, or anything that might deviate from formula. Its scenes, invariably two to four pages long, follow a predictable pattern: Dylan arrives, acts enigmatic, while others gaze at him in wonder. Dylan: reaction shot: Dylan. A Complete Unknown doesn’t liberate its audience from contemporary studio logic. It traps us within it, offering a portrait of the young artist as a young man that is far too tidy, too safe, and too afraid to embrace the ontological possibilities of cinema.

When even Bob Dylan, master of self-invention and artistic shapeshifting, gets flattened into a predictable sequence of close-ups, we can see how thoroughly our cinematic imagination, and technique, has atrophied. What's missing from contemporary cinema isn't just authenticity or artistry, but the fundamental openness that allows new worlds to emerge. Dylan’s songs, for instance, are themselves open–capable of endless adaptation both by Dylan himself and other artists; early Dylan–even as covered by Chamelet in Dylan drag — is the most interesting part of Complete Unknown. If there’s one film from late 2024, early 2025 that does this, it’s RaMell Ross’s Nickle Boys — which actually takes an interest in how its protagonists see and feel in ways that might diverge from the phenomenology of 2025.

Instead of creating cinematic sequences whereby different modes of existence might disclose themselves, and shock us out of our own over-optimized, phone-addicted states, the current filmmaking apparatus — the grammar of streaming era Hollywood — with its suffocating design and storytelling imperatives, has sealed off every offramp away from the present. The past — really, any fictional alternative — becomes not a realm of possibility to be discovered, but another product to be optimized.

Wisdom of Crowds is a platform challenging premises and understanding first principles on politics and culture. Join us!

This kind of writing is why I subscribe. Opinionated and well argued. If you care about cinema and you're fortunate enough to live in the vicinity of an independent cinema, I implore you support it by paying to watch films there. You won't regret it!

THANK YOU! So bored with so much “content“ these days