Welcome to CrowdSource, your weekly guided tour of the latest intellectual disputes, ideological disagreements and national debates that piqued our interest (or inflamed our passions). This week: AI, economic growth and human beings.

Join us! CrowdSource features the best comments from The Crowd — our cherished readers and subscribers who, with their comments and emails, help make Wisdom of Crowds what it is.

The Future Is Almost Here

A cryptic post from New York Times columnist Ross Douthat:

Nick Land. Douthat’s post alludes to the philosophy of an idiosyncratic British thinker named Nick Land, who believes that capitalism (and its main method of expansion, technology) is an alien force from the future, reaching backwards in time in order to dominate humanity.

“Machinic Desire.” A relevant quotation, from Land’s 1993 essay, “Machinic Desire”:

Machinic desire can seem a little inhuman, as it rips up political cultures, deletes traditions, dissolves subjectivities, and hacks through security apparatuses, tracking a soulless tropism to zero control. This is because what appears to humanity as the history of capitalism is an invasion from the future by an artificial intelligent space that must assemble itself entirely from its enemy’s resources.

“The Faith of Nick Land.” Compact’s Geoff Shullenberger recently published an excellent primer on Land’s thought.

“It’s Time to Build.” Venture Capitalist Marc Andreessen, a major investor and booster of AI companies, cites Land as an inspiration for his 2023 “Techno-Optimist Manifesto.”

Upshot. Douthat’s allusion to Land is a clever way of asking: is this long-foretold event — the replacement of human workers with machines — finally taking place?

Relevant Data:

Unemployment is at a four-year high.

Blue Collar Jobs. “It’s not just that total manufacturing employment is shrinking. The number of manufacturing sub-sectors that are adding jobs is rapidly shrinking,” says Bloomberg’s Joseph Weisenthal.

White Collar Jobs. “Americans with four-year college degrees now account for a record 25.3% of U.S. unemployment,” according to Hedgeye Risk Management.

Are Robots Taking Our Jobs?

Some views.

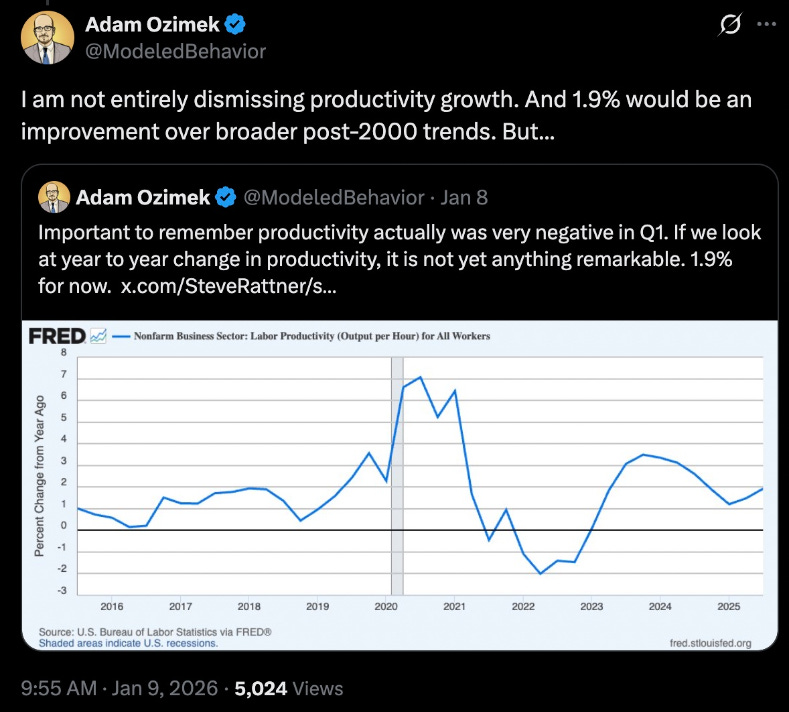

Productivity Growth Isn’t Actually That High. Replying to Douthat’s post, economist Adam Ozimek writes:

Robots Are Not Taking Our Jobs (Yet). Zanna Iscenko, AI & Economy Lead, Chief Economist’s Team, Google; and Fabien Curto Millet, Chief Economist, Google, study the numbers and conclude:

The most plausible explanation is that the data patterns observed are not early warnings of large-scale technological displacement, but rather the predictable consequences of a classic macroeconomic shock: the sharpest monetary policy tightening cycle in four decades.

We Will Soon Want Robots To Take Our Jobs. American Enterprise Institute scholar James Pethokoukis sees the matter differently: the coming demographic crunch and subsequent shrinkage of the workforce will force many industries to adopt AI robots:

Their argument isn’t that robots will replace people. It’s that in a world where new people are increasingly scarce, robots may be the only way to keep economies growing at all.

Almost everything people ever did in the ancient times is automated — and yet the world today now has more preferences to satiate and problems to solve than ever. The world hasn’t yet shown signs of coalescing to a great unification or a fixed state! Of course it’s conceivable that at sufficient capability levels, the generative process exhausts itself and preferences stabilize — but I’d be surprised.

Human Workers Will Get Blamed For Robots’ Mistakes. Cory Doctorow argues that human workers will become more vulnerable as they become responsible for AI robots’ mistakes:

“And if the AI misses a tumor, this will be the human radiologist’s fault, because they are the ‘human in the loop.’ It’s their signature on the diagnosis.”

This is a reverse centaur, and it’s a specific kind of reverse-centaur: it’s what Dan Davies calles an “accountability sink.” The radiologist’s job isn’t really to oversee the AI’s work, it’s to take the blame for the AI’s mistakes.

This is another key to understanding — and thus deflating — the AI bubble. The AI can’t do your job, but an AI salesman can convince your boss to fire you and replace you with an AI that can’t do your job. This is key because it helps us build the kinds of coalitions that will be successful in the fight against the AI bubble.

Last Resort? On October of 2024, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman said that selling ads would be the “last resort” business model for his company. On Friday, he announced that OpenAI will begin to sell ads. George Mason University economist Alex Tabarrok quips: “This is the strongest piece of evidence yet that AI isn’t going to take all our jobs.”

What Will We Do With All That Free Time?

Pondering a post-work future, I wrote last year:

Consider this counterfactual: what if in the last century, we had worked and developed our technologies under a different idea of what the purpose of human life is? If we had, would our tech today be any different? We have built hardware and software, apps and AI, with the idea of making it easier for us to accomplish our work. But what if work is not the only thing we should be thinking about?

Put another way: if we had labored under the idea that the purpose of human life is the pursuit of, say, beauty (rather than work), would technology look different today? Would buildings look any different? Would society as a whole? We have had an implicit understanding of the purpose of human life, and it’s this: the purpose of our lives is labor. Labor for the sake of what, exactly? The answer is unclear. But the fact that we can’t imagine a meaningful life without work suggests, at the very least, that we have a lot of thinking to do.

From the Crowd

This week, CrowdSource has a question for the Crowd. Specifically, for Ted Gioia, jazz historian and Substack’s The Honest Broker.

Ted cites CrowdSource in his recent post about Romanticism, titled “25 Theses about the New Romanticism.” Gioia believes that Romanticism will be “a healthy corrective” to the “Rationalism” of the AI era. So I want to take this opportunity to ask Gioia a question that’s been nagging me since 2019, when Gioia appeared on Tyler Cowen’s podcast to discuss music.

Gioia told Cowen:

We accept this so instinctively that we don’t even think twice. When you go to the orchestra, the first thing they do is tune up. Well, in the 20th century with this infusion from blues and jazz, you could play notes that were no longer in tune. You could bend the note. You could distort the sound, and this was an amazing reversal of 2,500 years of mathematical Pythagorean music.

[…] So you had a reversal in the 20th century with the advent of black music, but now that’s dying out in many ways. Just auto-tune — the idea is every note’s going to be perfectly in tune. Or a lot of this digital music — everything is perfectly in tune, and the bent blues notes are disappearing.

Here’s my question for Gioia: Does he see a link between his political concerns (about AI) and his musical tastes (about bent notes). Does a free society need popular music with bent notes? Does resisting the Machine require a new rhythm? Will the new Romanticism bounce and swing?

See you next week!

Wisdom of Crowds is a platform challenging premises and understanding first principles on politics and culture. Join us!

I think my argument here is a good counter to the "robots are taking our jobs" perspective. https://hollisrobbinsanecdotal.substack.com/p/llms-are-lagging-indicators

The intellectual debate is a bit broader than what the usual bro suspects are saying...