Welcome to CrowdSource, your weekly guided tour of the latest intellectual disputes, ideological disagreements, and national debates that piqued our interest (or inflamed our passions). This week: intelligence, artificial and human.

Join us! CrowdSource features the best comments from The Crowd — our cherished readers and subscribers who, with their comments and emails, help make Wisdom of Crowds what it is.

What AI Can’t Do

“The minerals are about AI,” Trump said about the US-Ukraine minerals deal. We need a new “Manhattan Project for AI,” says Palantir CEO Alex Karp, in his new book.

In this context, the takes about what AI cannot do are accumulating. Some memorable ones:

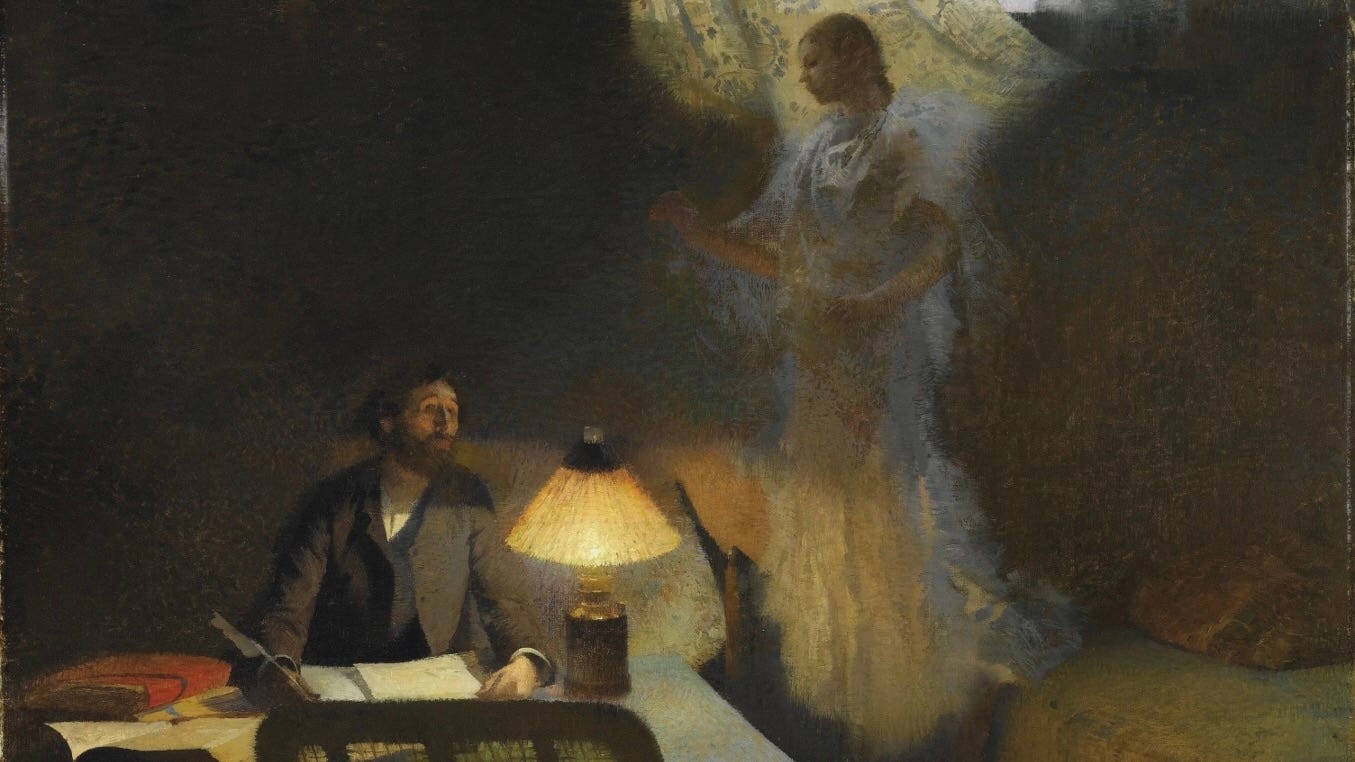

AI Can’t Free Associate. New School professor Eli Zaretsky writes: “Computers have had no infancy, therefore no primary process, and no free associations because they have nothing to free associate to. … [C]omputers have no inner world to discover.”

AI Can’t Use Language. New Yorker writer Ted Chiang argues: “A dog can communicate that it is happy to see you, and so can a prelinguistic child, even though both lack the capability to use words. ChatGPT feels nothing and desires nothing, and this lack of intention is why ChatGPT is not actually using language.”

AI Doesn’t Have a Direct Sense of Objectivity. So argues Ted Gioia. Everything AI “knows” is mediated, through data — not immediately perceived, as with human perception.

AI Can’t Draw Caricatures. Writer Freddie DeBoer says: “[A] human illustrator can render a vastly more convincing likeness than a hideously expensive machine learning system.”

What Computers Can’t Do

The godfather of what-AI-can’t-do is the late philosopher and UC Berkeley professor, Hubert Dreyfus.

Surprise! In 1965, a young Dreyfus worked for the Rand Corporation on a project about the feasibility of human-level artificial intelligence. To the chagrin of the folks at Rand, Dreyfus concluded that computers would never be able to fully mimic human behavior.

Three Things AI Can’t Do. In his 1965 report, Dreyfus identifies three processes that AI can’t replicate: “fringe consciousness, essence/accident discrimination, and ambiguity tolerance.”

Mindless Coping. In later works, like What Computers Can’t Do (1978), Dreyfus argues that computers don’t experience the world the way a human being does.

“Mindless coping” is Dreyfus’ term for the way humans dwell and know the world in an intuitive, non-conceptual way.

Computers, Dreyfus says, will never “mindlessly cope” in the world. Their knowledge is always mediated by data processing.

An example of mindless coping might be the way, after a lot of practice, we can ride a bike without having to think about what we’re doing.

Of Two Minds

Zaretsky writes: “It is difficult to distinguish human from machine intelligence because we use the same underlying philosophical and psychological understandings of the mind to discuss both.”

Alternatives. For Zaretsky, a better philosophical/psychological frame for understanding human intelligence would be psychoanalysis. For Dreyfus, it’s a philosophy known as phenomenology.

L’esprit de finesse. Another fruitful framework is French thinker Blaise Pascal’s distinction between the two ways human intelligence works: the “geometric” mind (l’esprit géométrique) and “intuitive” mind (l’esprit de finesse).

The geometric mind is methodical and demonstrative. It starts from fixed premises, works step by step toward logical conclusions.

The intuitive mind grasps many premises at a glance, and can jump to a conclusion without too many steps. It is akin to “mindless coping.”

Dreyfus applies Pascal’s framework to machines: they can only ever have a geometrical mind.

From the Crowd

Shadi’s article about J. D. Vance’s Munich speech generated a lot of comments, and two substantive threads:

An intense debate about the recent cancellation of the Romanian elections, between Shadi Hamid and florian robicsek.

A fruitful back-and-forth between socialist critic George Scialabba and Shadi Hamid about freedom of speech and Europe.

Sometime contributor to Wisdom of Crowds Haroon Moghul’s insightful reflection on Santiago Ramos’s essay about the New Right:

I haven’t read much of BAP, so I don’t know if it would be unfair to point out another apparent inconsistency in the way he lauds Stroessner — the failure to notice, or perhaps the choice to ignore, ordinary causality and clear dependency? It seems that, in addition to the principles at work which the New Right would rather we not notice, as you carefully note, the valorization of Stroessner is additionally contingent on our overlooking what was actually happening in the world. Bronze Aged he might be, but this was the post-war order.

As you wrote, after all, the withdrawal of US support eventually brought the whole thing crashing down. If Stroessner was a “great” and “free” man, a “warrior,” it's curious that his greatness, freedom and ferocity were only achieved in alliance with a nation founded on the very principles, restrictions and limitations BAP apparently spurns. Remove the US from the picture and, well, he eventually came down. One could say the same about many of the purportedly great men of history, whose greatness was ultimately subordinate to the messy work of institutions and the embarrassing ideals of aspirational democracies

If I were more perverse, one might even note that some men who think themselves great are in fact simply prominent because they have manipulated a system that otherwise generated great wealth; should they come to power in such a system, they would be unable to sustain it, let alone extend it, and given enough time and absent enough resistance, bring the whole edifice down. I think it was in Simon Montefiore’s recent work The World: A Family History of Humanity in which I read a description of Emperor Trajan’s unique qualities of leadership: vision, acumen, resources. But where do these resources come from, I suppose, is the question nobody wants to answer.

See you next week!

Wisdom of Crowds is a platform challenging premises and understanding first principles on politics and culture. Join us!

Clearly computers are not conscious now, and we can't be sure they ever will be. But then, at a certain point in our evolution, humans couldn't speak, draw, or reflect and arguably had no inner life. How did we come by these things. Through emergence, the production of novelty by increasing complexity. As computers become more and more complex and lifelike, they may eventually become life forms. Doubtless very different life forms from us, but capable of analogues of human thinking and feeling. If it happens, it will probably be a long way off, so there's no penalty for scoffing at the prospect now, except being scoffed at posthumously if it does happen.