Welcome to CrowdSource, your weekly guided tour of the latest intellectual disputes, ideological disagreements and national debates that piqued our interest (or inflamed our passions). This week: conversations about the Great Conversation.

Join us! CrowdSource features the best comments from The Crowd — our cherished readers and subscribers who, with their comments and emails, help make Wisdom of Crowds what it is.

The Death of a Liberal Arts Program

“The tragedy of the contemporary academy is that even when traditional liberal learning clearly wins with students and donors, it loses with those in power.”

So wrote Jennifer Frey last week in the New York Times, in an article lamenting the closure of the University of Tulsa’s Honors College, where Frey was inaugural dean.

The Honors school at Tulsa was grounded in what is known as the “Great Books” curriculum, AKA the “Great Conversation”:

.. we invited our students to enter “the great conversation” with some of the most influential thinkers of our inherited intellectual tradition. For their first two years they encountered a set curriculum of texts from Homer to Hannah Arendt. These texts were carefully chosen by an interdisciplinary faculty because they transcend their time and place in two senses: They influenced a broader tradition, and they had the potential to help our students reflect in a sustained way on what it means to be a good human being and citizen. Our seminars were led by faculty members who did not lecture or use secondary sources. Rather, the role of the faculty members was to foster and guide conversations among our students that allowed them to think through these questions for and among themselves.

What is a “Great Books” education?

From Homer to Hannah Arendt

The overarching goal of a Great Books education has always been to show students “the best that is known and thought in the world,” as Matthew Arnold put it, or “from Homer to Hannah Arendt,” as Frey wrote.

The Great Books began as an idea, became a movement, and matured into institutions.

An Idea. In 2021, Louis Menand wrote about the origins of the Great Books idea in America: “The idea of the great books … were for adults who wanted to know what to read for edification and enlightenment, or who wanted to acquire some cultural capital.”

A Movement. In the 1920s, professors Robert Maynhard Hutchins, Mortimer J. Adler and Mark van Doren, among others, were behind the creation of “the Great Conversation” — a foundation with a set of books that would inform ambitious learners for a hundred years.

Institutions. Other Great Books-oriented institutions include universities like Thomas Aquinas and St. John’s (in Annapolis and Santa Fe), the Core Curriculum at Columbia and the Standard Liberal Education program at Stanford, volunteer-run centers like the Catherine Project and podcasts like Ascend and Frey’s own Sacred and Profane Love.

The Aspen Institute, a Wisdom of Crowds partner, has its roots in this Great Books movement.

Canon Controversies

The Great Books is not a set of dogmas or a political program, and its proponents disagree about a lot.

There are lively discussions — about pedagogy, curricula and which books deserve to be called “Great.” Some recent ones:

Expanding the Canon. Here’s an illuminating exchange between St. John’s-Annapolis professor Zena Hitz and Tanner Greer of The Scholar's Stage about which 20th century scientific texts should be included in the Great Books canon:

… ideas about systems, modeling, complexity, criticality, hierarchy, evolution, computability, information, adaptation, and strategic interaction — are things that will be remembered as the “great ideas” of the 20th century a few centuries from now …

“We Can Only Keep Humanity Alive By Reading One Another.” Author, professor and songwriter Anika Prather argues for the inclusion of the Black intellectual tradition in the Great Books canon:

“What’s Wrong with History?” Here’s Zena Hitz’ contribution to a longstanding debate within Great Books circles, about whether historical context is essential for understanding the Great Books:

The Classics: Pro and Con. 2021 saw a subterranean disagreement between professor Dan-El Padilla (of Princeton) and Roosevelt Montás (then a professor in the Columbia Core Curriculum).

“A Different Order”

To get an idea of what a Great Books course is like, read Thomas Merton’s account of taking Mark van Doren’s Shakespeare course at Columbia in the 1940s:

It was the best course I ever had at college. And it did me the most good, in many different ways. It was the only place where I ever heard anything really sensible said about any of the things that were really fundamental — life, death, time, love, sorrow, fear, wisdom, suffering, eternity. A. course in literature should never be a course in economics or philosophy or sociology or psychology: and I have explained how it was one of Mark’s great virtues that he did not make it so. Nevertheless, the material of literature and especially of drama is chiefly human acts — that is, free acts, moral acts. And, as a matter of fact, literature, drama, poetry, make certain statements about these acts that can be made in no other way. That is precisely why you will miss all the deepest meaning of Shakespeare, Dante, and the rest if you reduce their vital and creative statements about life and men to the dry, matter-of-fact terms of history, or ethics, or some other science. They belong to a different order.

“The Day No One Would Say the Nazis Were Bad.” This essay by philosopher, Wisdom of Crowds friend and St. John’s grad Mary Townsend showcases the Great Books approach in a more recent setting.

Alternative for Tulsa

Those so inclined may sign a petition calling for the reinstallation of Tulsa’s Honors program.

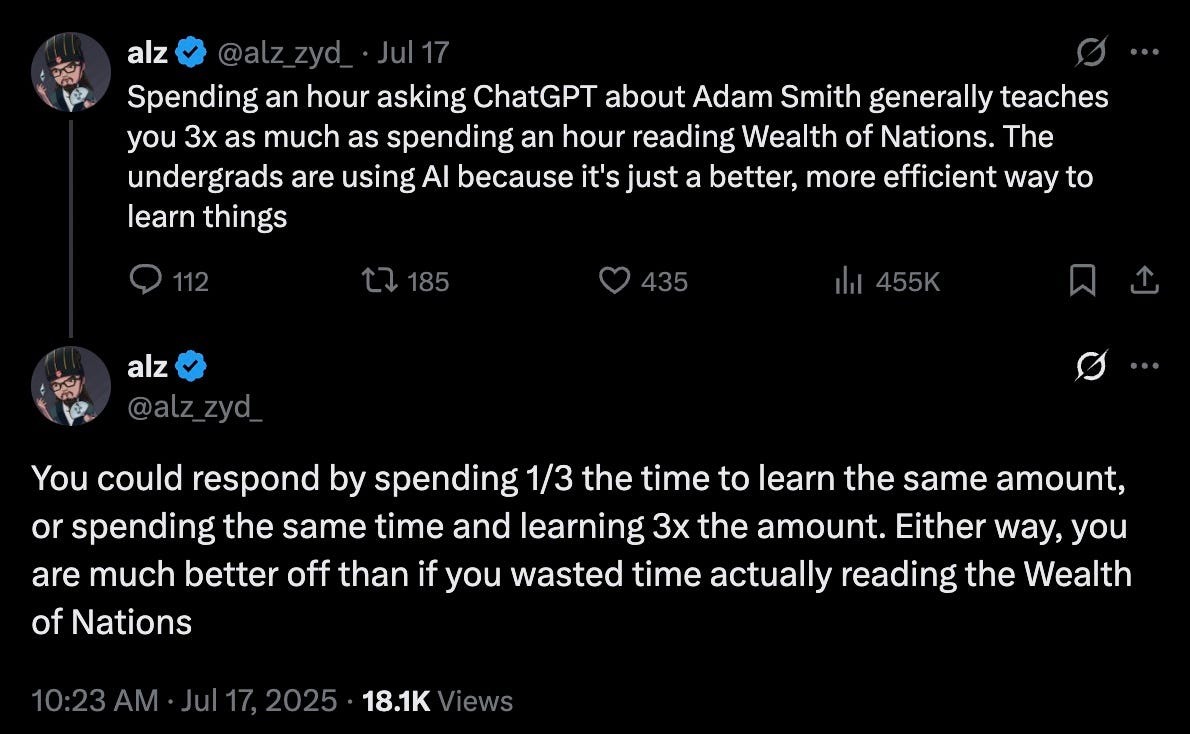

The ultimate alternative to such programs — and the Great Books method — might be presaged in this X post from last week:

From the Crowd

Reminder: Shadi’s New Book is Coming! The Case for American Power by

Shadi Hamid comes out on November 11. It’s not too early to pre-order!

Overton Window Shift. Responding to Shadi Hamid’s latest essay, RC talks about being on a visa as a foreigner in the United States:

I am not defending what ICE did to the Irish tourist, but I’ll say this. When I came to the US on student visa in 1994, I was paranoid of being out of status. After finishing graduate studies I worked on F1 (1 year work permit all international students get) visa and transitioned to an H1B visa before the F1 expired. I changed jobs multiple times and each time I ensured I was never out of status, and finally got my Green card in 2002. I feel things got really lax and people have been no longer worrying being out of status, as evidenced by the example of the Irish tourist (though I get it he was sick and that is why he ended up out staying the visa by a mere 3 days).

I think the Trump administration goal is to change the Overton window — that non-citizens and permanent residents can no longer have a lackadaisical attitude on being on a valid visa, and more generally visitors to the US need to be more careful on how they engage on political issue on campus or otherwise.[…]

The Difficulty of Making Anti-Trump Art. Gemma Mason adds to the discussion that Damir Marusic and Santiago Ramos had with Paul Elie in our last podcast:

[…] I wonder if the comparative lack of protest music against Trump is partly because Trumpism is already, in itself, something of an anarchic cry against the system. Kind of like a synthesis between the Moral Majority and punk rock, if anything, weird as that sounds.

I can think of a couple of songs that might qualify. Sara Bareilles’ “Armor” was written after the Women’s March, for example. And Brandi Carlile’s “Sinners, Saints and Fools” is a pretty powerful commentary on immigration politics.

Bareilles and Carlile are both Christian. Are their songs? I’m inclined to categorise “Armor” as crypto-religious, referencing Adam and Eve to make a cultural statement. On the other hand, “Sinners, Saints and Fools” is straightforwardly Christian, if you ask me.

Trump can’t be resisted from a standpoint of lawlessness; that only feeds him. Likewise, standard political posturing tends to fall flat. Only critiques from a broader ideology that is not solely political seem to stick. The Effective Altruist reaction to the dismantling of USAID had some staying power because it was coming from people who were obviously willing to sacrifice something to the principles they were invoking. Likewise, I suspect the Christian convictions of Bareilles and Carlile are of help, here.

See you next week!

Wisdom of Crowds is a platform challenging premises and understanding first principles on politics and culture. Join us!

Thomas Merton may not be the typical undergraduate, but I was glad to see his reminiscences about Mark Van Doren and the influential Columbia Western Civ program. They are just one example of how these programs guide and illuminate one’s life.

Everyone seems to write about the same books and the same conversations when there are so many more out there. Here's our Great Books/Great Science Books sequence at Utah, for example. https://humanities.utah.edu/perspectives/2023-2024/great-books-returns.php And while the recording doesn't seem to be available any more this was an awesome conversation about the Black Literary & Philosophic tradition. https://ah.a7prd.sonoma.edu/spotlight/dean-hollis-robbins-participates-university-chicago-philosophy-departments-night-owls