Welcome to CrowdSource, your weekly guided tour of the latest intellectual disputes, ideological disagreements, and national debates that piqued our interest (or inflamed our passions). This week: death and politics.

Join us! CrowdSource features the best comments from The Crowd — our cherished readers and subscribers who, with their comments and emails, help make Wisdom of Crowds what it is.

“Necropolitics” — An Idea Whose Time Has Come

In 2003, the Cameroonian political thinker Achille Mbembe coined the term “necropolitics” to describe “those figures of sovereignty whose central project is not the struggle for autonomy but the generalized instrumentalization of human existence and the material destruction of human bodies and populations.”

Sources of Legitimacy. In other words, necropolitics describes the strategy of claiming political legitimacy not through protecting liberty and rights, but by flexing muscles over life and death.

Sovereignty in Action. As Mbembe puts it: “the ultimate expression of sovereignty resides, to a large degree, in the power and the capacity to dictate who may live and who must die.”

Today, “necropolitics” is starting to sound like the word for our time:

Death Incentive. Consider this piece describing how the Russian state leverages economic incentives — including a hefty death compensation — to boost military recruitment:

In some of the country’s poorest regions, a military wage is as much as five times the average. … These are life-changing sums for those left behind. … [T]he family of a 35-year-old man who fights for a year and is then killed on the battlefield would receive around 14.5 million rubles, equivalent to $150,000, from his soldier’s salary and death compensation. That is more than he would have earned cumulatively working as a civilian until the age of 60 in some regions.

Collateral Damage. Consider, too, how nuanced talk about proportionality, collateral damage, and civilian casualty rates is often replaced by the blunt question of whether the state has the right to kill civilians “if necessary.” Some recent examples:

“Get it Over Quick.” Congressman Tim Wahlberg of Michigan invoked the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as sound military strategy, to a be applied against Hamas and Russia.

“Justified and Moral.” Israeli Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich declared that withholding humanitarian aid might be justified to defeat Hamas.

“Assisted Dying.” Finally, consider the legalization of assisted suicide this past week in the United Kingdom.

Is this Necropolitics?

On Saturday, British lawmakers legalized assisted suicide. Is this an example of necropolitics? Could Mbembe’s idea help explain the trend toward legalizing assisted suicide spreading throughout wealthier nations?

Freedom to Choose. Supporters of the UK bill often appealed to freedom of choice.

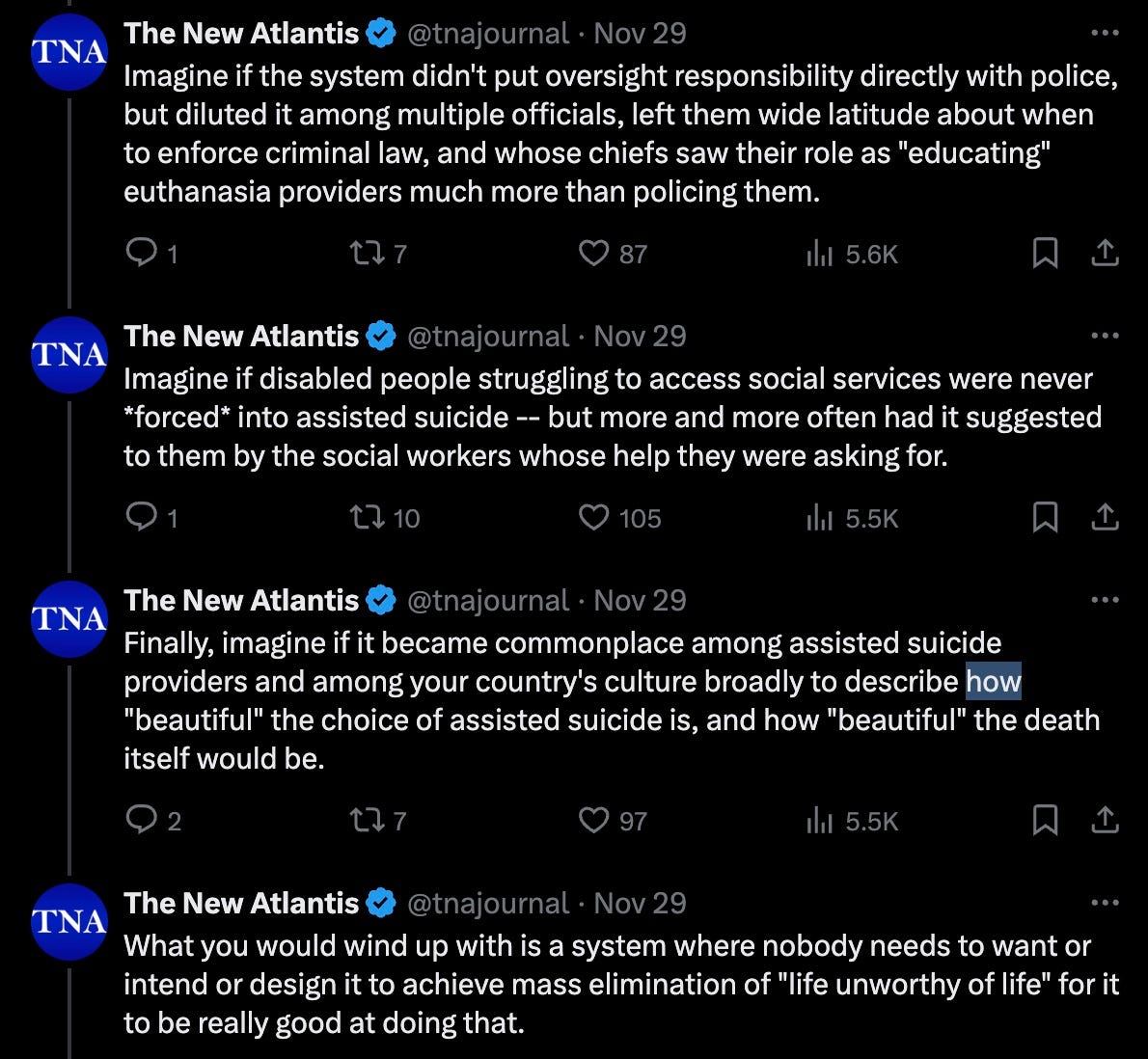

Coerced Choice? New Atlantis editor Ari Schulman argues that the legalization of assisted suicide will result in a society where the old and infirm feel pressured to choose to die:

Death Incentive (II). Echoing Schulman’s point, reporter Madeleine Kearns interviewed disability rights activists who worry that that legalization of assisted suicide will “make it look perhaps increasingly selfish to stay alive in an expensive way,” since ending their care would save the health system money.

Cost-Cutting. The financial incentive is, in the UK at least, confirmed in this 2022 report by The Lancet Commission on the Value of Death: “between 8 percent and 11 percent of annual health expenditure for the entire population is spent on the less than 1 percent of people who die in that year.”

Under necropolitics, says Mbembe, people become “living dead.” They exist in a half-alive, fearful state because they know they live at the mercy of the powerful.

Present-Day Necropolitics. In his 2019 book, Mbembe’s go-to example of present-day necropolitics is modern warfare conducted through proxies and aerial bombing.

This is what a Necropolitical Future Might Look Like: a free society with permissive assisted suicide laws and with a new class of “living dead” — old and/or infirm citizens who feel a slight tug (from both the state and society at large) toward suicide.

From the Crowd

Mary Jane Eyre comments on last week’s essay by Gemma Mason:

Beautiful piece. For me the following sentence points to the limits of the porous/buffered self dichotomy: “Even a buffered self still feels influenced by different forces.”

From the perspective of no-self spiritual traditions, the fiction of angels and demons and God flows ultimately from the fiction of the self. But fiction has its uses.

Personally, I don’t think the no-self notion is very helpful, pragmatically speaking. Even if life is but a dream, it certainly feels real for as long as we are living it. I think a viewpoint that is in some ways similar to that of the porous self, but that does not necessarily require a belief in extra sensory perception, is Martin Buber’s relational self: it only makes sense to think of the self in relation to an other.

See you next week!

Wisdom of Crowds is a platform challenging premises and understanding first principles on politics and culture. Join us!

Two buckets here: 1) The right of the state to defend or exert its will against the 'other'. 2) The inherent need of the state to uphold the flourishing of its citizenry. If the state fails in either endeavour, it won't exist for long.

As for the right to die, there's nothing new there. What's remarkable is the insistence that dying be removed from its ugliness and pain. Any cancer patient can starve themselves to death. But when we remove the discomfort and social stigma, well the state isn't long for this world.

All of this has the bad taste of A. Huxley, though I can't recall if he addresses this directly, the subdued masses he describes are certainly the flavor of European stagnation these days. A war with Russia may set them straight, a trade war with the U.S. will not.

In the UK assisted suicide is seen as the pinnacle of secular freedom of choice; a victory against religion which is weird really since in the UK religion isn't much of a thing. The Brits really don't like disabled people, adults or children and are not quite sure about the elderly - the protestant work ethic runs so deep that even those who clearly cannot work are viewed with deep suspicion, even if it's your elderly Mum. The failure of what was the liberal left, Social Justice Warriors or the Woke to have any concern for or the most vulnerable in British society is chilling in it's affect and is not unmissed.