Why Decline Is Never Inevitable

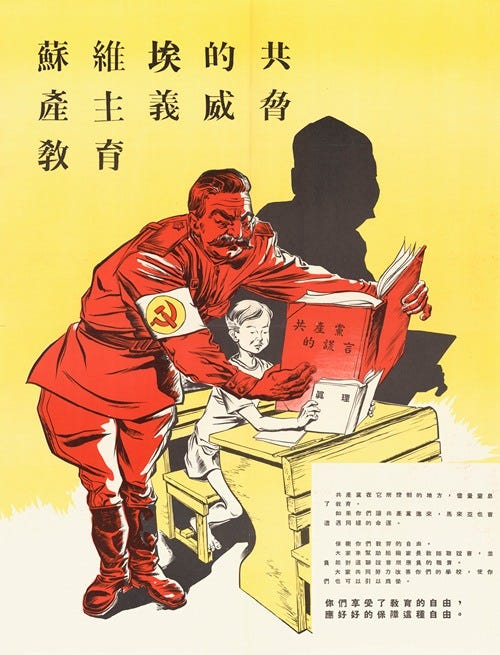

When we talk about decline, we need to ask—relative to what? American intellectuals overestimated the Soviet Union. Now it's China.

Editor’s Note: We want to remind you that in addition to the audio of our podcast, video will be a standard feature of new episodes. Because facial expressions can say a lot. For a taste, watch “Among the Unbelievers”—one of our most personal episodes yet where we discuss free will, God, dating apps, and the search for meaning. Become a paid subscriber …