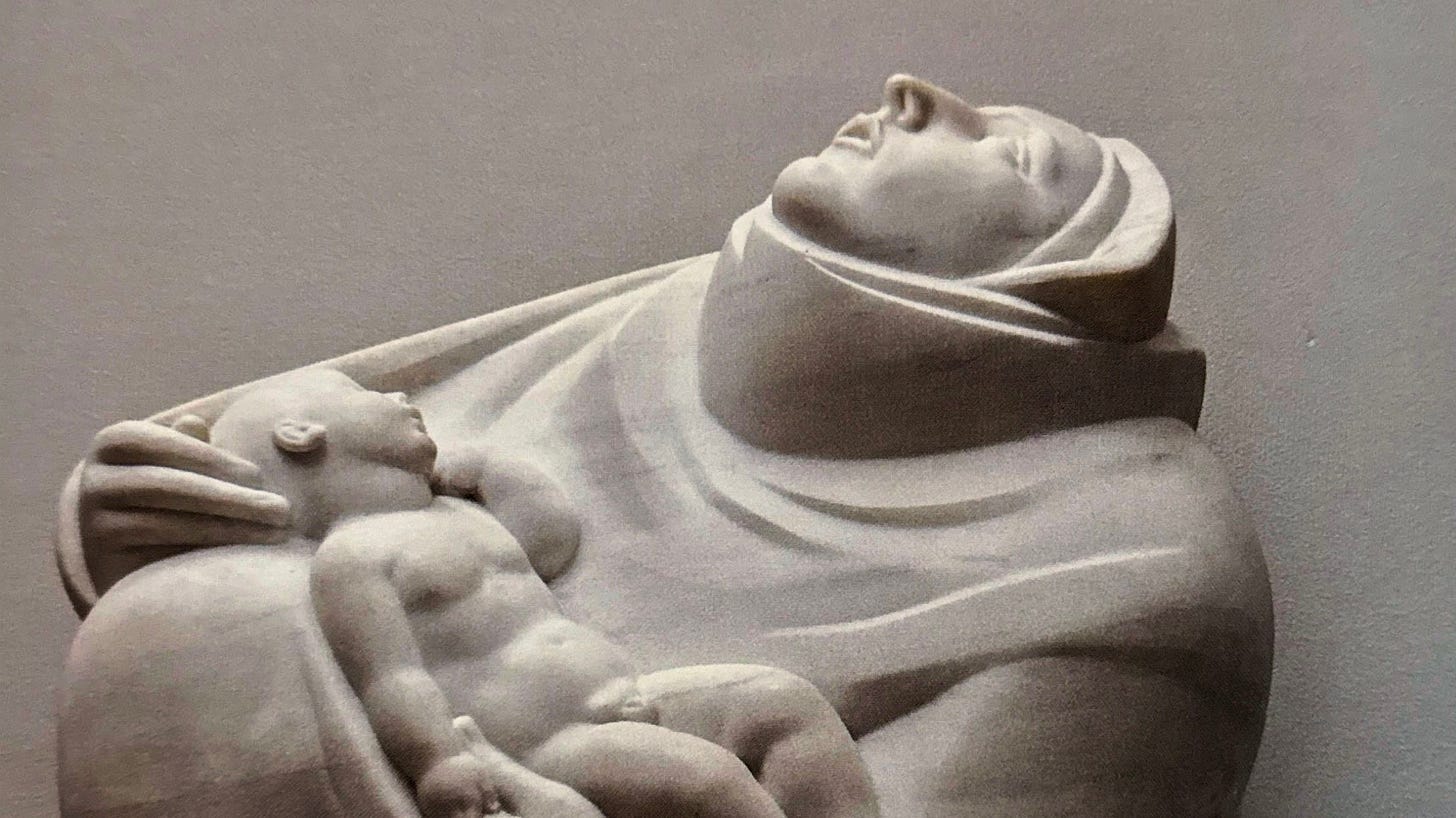

This week, I was taken by a remarkable review essay in the London Review of Books by James Butler titled “Trivialised to Death”. What sucked me in before reading a word was the painting sitting up top of the page: Caravaggio’s “Sacrifice of Isaac.”

I’m not sure when I saw my first Caravaggio in person. I want to…