The End of History Dies Hard in Berlin

Are Germans still too optimistic about the future, despite everything?

If history had ended in 1989, it would have ended in Berlin. I often think of this city, where I live, as a monument that sprung up in the place where history collapsed, like a cathedral to a martyred saint. This is not even really a matter of metaphor: after World War II, Berlin was carved up into an American sector, a Soviet sector, a British sector and a French sector, all poised to face off against each other until one of them crumpled.

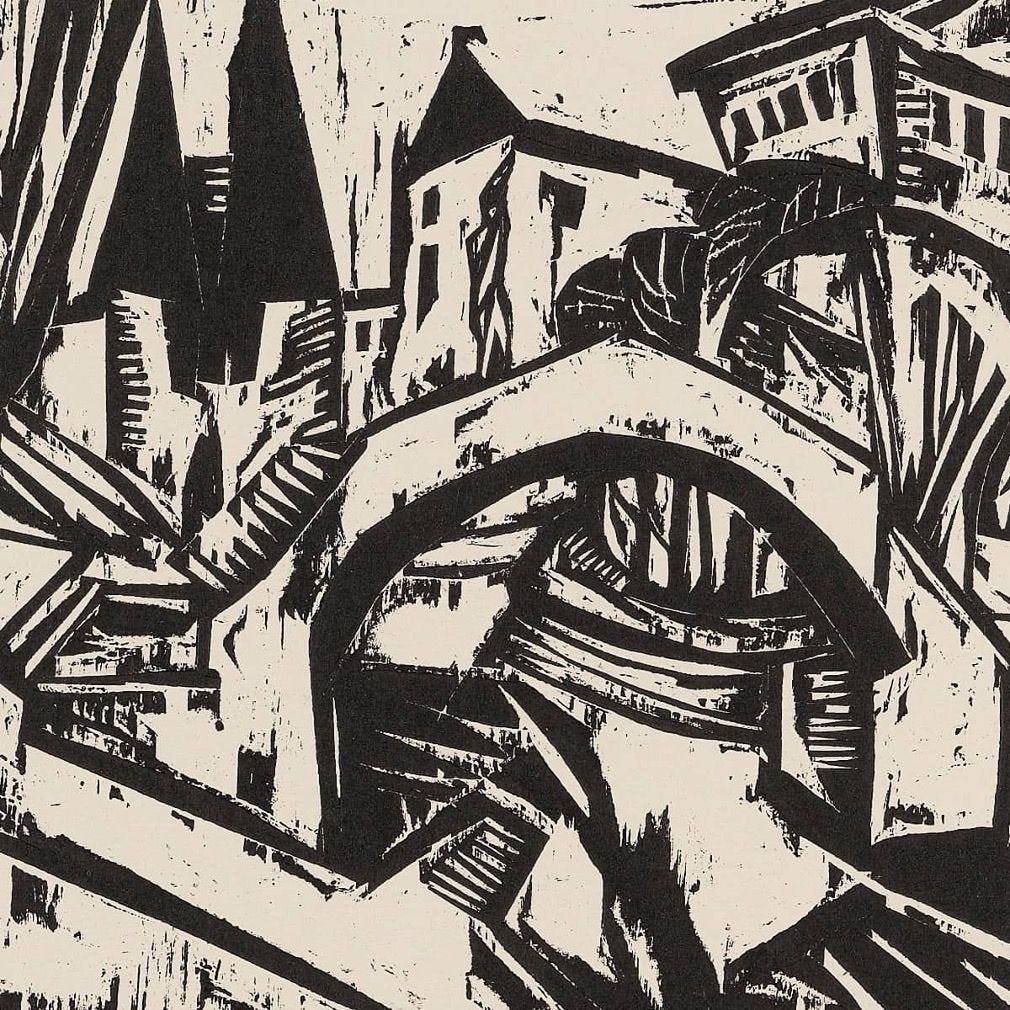

Today, there is a scar that runs across the streets and along the sidewalks where the Berlin Wall once stood. In the meantime, the 20th century inscribed itself on the city's architecture, which now appears like a cross-section of the last hundred years: there is the domineering Nazi neo-classicism from the 1930s, the triumphal Stalinist city blocks of the 1950s, the quiet bourgeois suburban style of West Berlin from the 1970s and '80s, the optimistic skyscrapers of the Sony Center that went up in the '90s. As an American, I sometimes find all this heavy imagery overbearing, as though I'm trapped on the set of an epic war movie.

Berlin has made for an eerie backdrop in the last month as Ukrainian refugees arrive here daily from neighboring Poland. The lower level of the central train station has been set up as a processing center with the usual German rigor: there are schedules announcing when trains come in; a line where arriving Ukrainians can get free train tickets to join family members in other parts of Germany; there is a covid testing station; tables with stacks of sandwiches, toothpaste, toilet paper, and cat food; a children's play area with toys and books.

German humaneness is learned from history. I wasn't yet living in Europe in 2015, when a large influx of refugees arrived from Syria, so I'm not able to offer a first-hand comparison. By all accounts, Germans largely supported the government's efforts to house and help Syrians at that time. But the asymmetry between the response seven years ago, and what has been a veritable public outpouring for Ukrainians, whom Germans are taking into their private homes, has been disheartening. Still, I would contend that there is a historical dimension to the discrepancy. The sight of mothers and children from Eastern Europe filling the train station in Berlin is a trigger for a memory that is not very distant, only a generation away for some Germans my age whose parents were themselves refugees. The destruction and dismemberment of Europe was not supposed to happen again.

Ideas about "civilization" are stricter and more uniform in Europe than in America, but Europeans regard it as more fragile, which seems to make it so. Germans, especially, believe that no matter how solid the order around us looks, it can disintegrate quickly. I have mostly found this irritating—what I call German "catastrophic," this culture of expecting that everything that one has can disappear in an instant. Recently, I began to wonder whether they weren't right. Berliners began buying iodine pills to take in case of radiation exposure. We woke in the middle of the night to the news that a nuclear reactor 1,200 miles away was on fire. Berlin itself is in the former East Germany, which was part of the Soviet sphere, and therefore potentially within the sights of a revanchist Putin. And the German military is notoriously ill-equipped. Americans have limited possibilities available to the imagination, whereas Germans can see foreign tanks rolling down their streets because it happened just a few decades ago. Everyone around me talked about war coming, perhaps first spilling over into Poland, then drawing Germany in too, as though it were the most natural thing in the world.