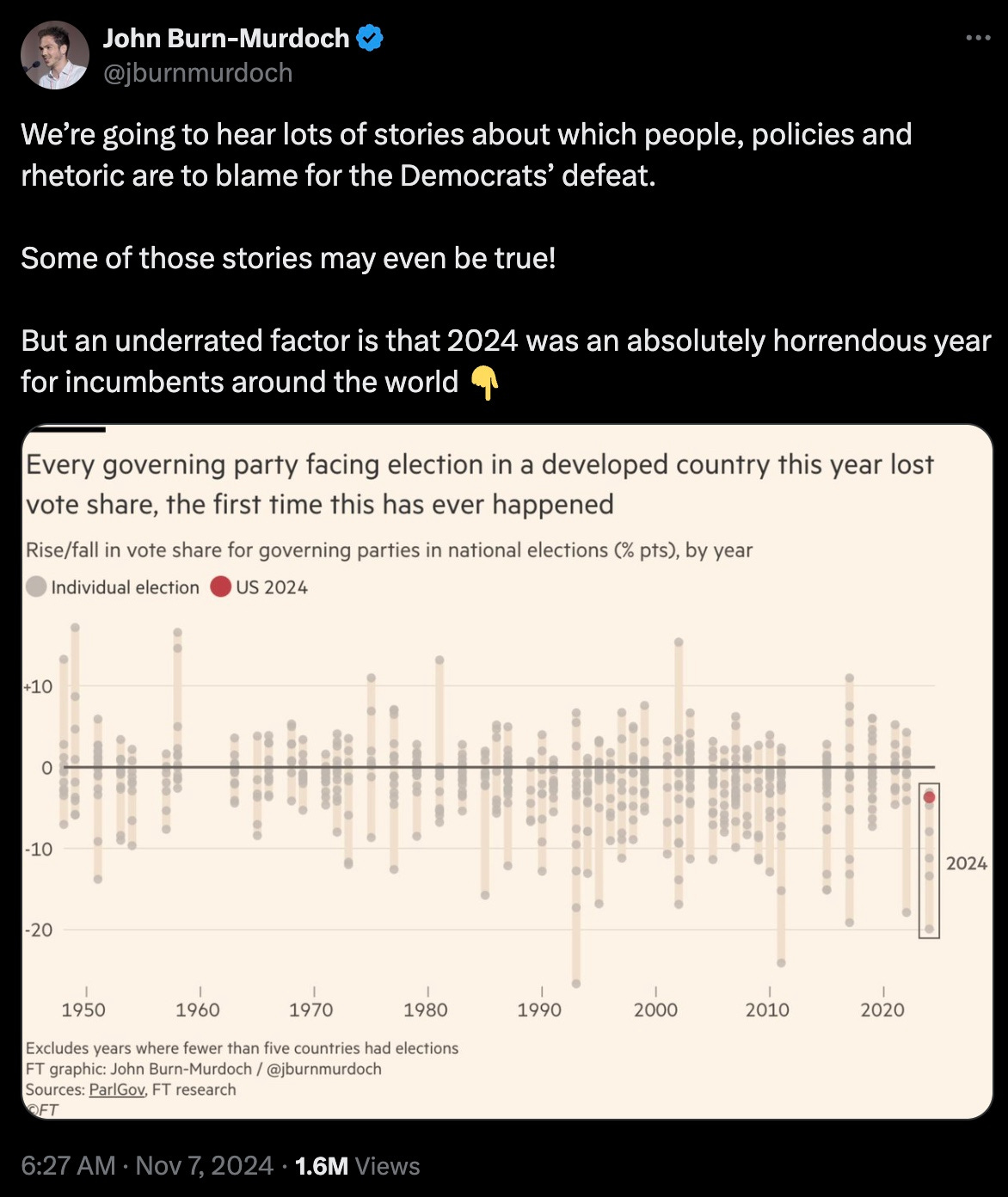

From the chief data scientist at the Financial Times, an interesting observation:

Burn-Murdoch sums it up: “Harris lost votes, Sunak lost votes, Macron lost votes, Modi (!) lost votes, as did the Japanese, Belgian, Croatian, Bulgarian and Lithuanian governments in elections this year. Any explanation that fails to take account for this is incomplete.”

So the Trump victory becomes less shocking within this context of declining incumbents. Or does it? Look at that chart again. Burn-Murdoch adds:

What looks like a trend in 2024 also looks like a unique moment in the history of modern democracy. In other words, one could say that Trump’s victory was somewhat predictable, given one observable trend in 2024. But that trend itself is surprising, given the last 120 years or so of data.

The above suggests that what might work as a predictive model for human behavior is too context-dependent to serve as a universal rule. No matter how granular the data gets, or how large our scope of space and time, human actions retain a kernel of spontaneity and unpredictability.

Friend of WoC Jason Blakeley puts it more philosophically in his book We Built Reality: How Social Science Infiltrated Culture, Politics, and Power: “Human social and political behavior … is not law-abiding or mechanistic in nature. … no set of antecedent conditions is ever sufficient to determine a consequent belief or action.”

It’s hard to escape the idea, though, that a hidden factor or group of factors might exist that would allow us to predict human behavior with a high degree of accuracy. But deep down we know that we are unpredictable even to ourselves. Consider this satirical video from The Onion, where a political analyst focuses on a single man, “an ordinary rustbelt body” who voted for Hillary in 2016 and Trump in 2020. The host asks: “What are you seeing inside this person that might indicate movement in one way or another?” The memories and feelings of that rustbelt body might tug it in one direction or another, but his vote — that is, his choice — is ultimately determined by “the Source, the origin of life, existence itself, where all of humanity’s answers can be found.”

The Onion video makes a metaphysical claim behind the cover of laughter: free will is an unfathomable mystery. Why? I don’t know for sure, but we should start by admitting that the mystery is there. The doomerism and pessimism that is everywhere around us, more so after the election, might be alleviated by remembering that we are free. The future need not be fully determined by today.

To see what I mean, watch this debate between Daniel Bessner (of

) and . Bessner makes a compelling analysis of our current political predicament. But then he comes up against the limits of his Marxist worldview: there is basically nothing we can do, he says, to stop “the mutual ruin of the contending classes.” If the workers’ revolution had started in the 19th century, in Germany or the United Kingdom instead of Russia, then modernity would have unfolded differently. As things stand today, Bessner argues, it is nigh impossible to halt the conflicts and transcend the contradictions of the global capitalist system.I don’t mean to dismiss Marxism. No one can doubt that some of the best historians of the last century were Marxists. There is a lot to be said for it as a theory. But the theory, while it can help us interpret the past, should be jettisoned if it keeps us from expecting something hopeful in the future. I know that if you believe the whole Marxist theory of history, then it is hard to see how things can turn out well in the next hundred years. But new figures can emerge, new technologies might be invented, new ideas can be conceived. In short, Marxism can be partially true, which means that it offers an incomplete picture of the world.

Since I don’t mean to pick on Marxists specifically, here is a neoliberal example of the same doomer determinism I am talking about. In 2022, after Colombians elected the socialists Gustavo Petro as president, David Frum and Anne Applebaum — leading lights of Atlantic magazine neoliberalism — were left perplexed:

It’s normal to be confused by an election outcome. But Applebaum here does not see her confusion as a reason to revisit her assumptions about what determines election outcomes. The problem must be that the voters did not get the message, or were somehow deceived. It could not be that the voters made a judgment call that neither Applebaum nor Frum anticipated, or can understand.

A bleak forecast can become less bleak if we factor in the mystery of free will and the likelihood that something unexpected can always happen — even something welcome and good.

This post is part of our collaboration with the University of Pittsburgh’s Center for Governance and Markets.

Wisdom of Crowds is a platform challenging premises and understanding first principles on politics and culture. Join us!

"...the theory, while it can help us interpret the past, should be jettisoned if it keeps us from expecting something hopeful in the future." Great truth claim.

"A bleak forecast can become less bleak if we factor in the mystery of free will and the likelihood that something unexpected can always happen — even something welcome and good."

I hadn't thought to go from free will to hope, but it's a neat way to say we can't account for all the possibilities, so let's at least be optimists. I tend towards finding more consolation in Shadi's ultimate judgement for the religious, but I like this. It fits nicely in the Faith, Hope, Love trifecta. I mean my hope is in ultimate judgement, but still.

"after Colombians elected the socialist **Gustavo Petro** as president". Francia Márquez is the VP.