According to ancient wisdom, we humans find lasting happiness only when we shrink our sense of self and its desires. When we reduce our wants, we reduce our frustrations, in this sun-whipped desert world of obstacles and lacks. Perhaps, done well, such an approach to life remains promising. But the life of sand and strife is not the one most readers find themselves in. While you likely face struggle and loss in many areas of your life, in many others you may find yourself with the opposite problem: verdant choice, abundant options, a forest of berries and wild game ready to be delivered to your apartment for a small fee, or for free if you had calculated that a subscription to a delivery service would save you money.

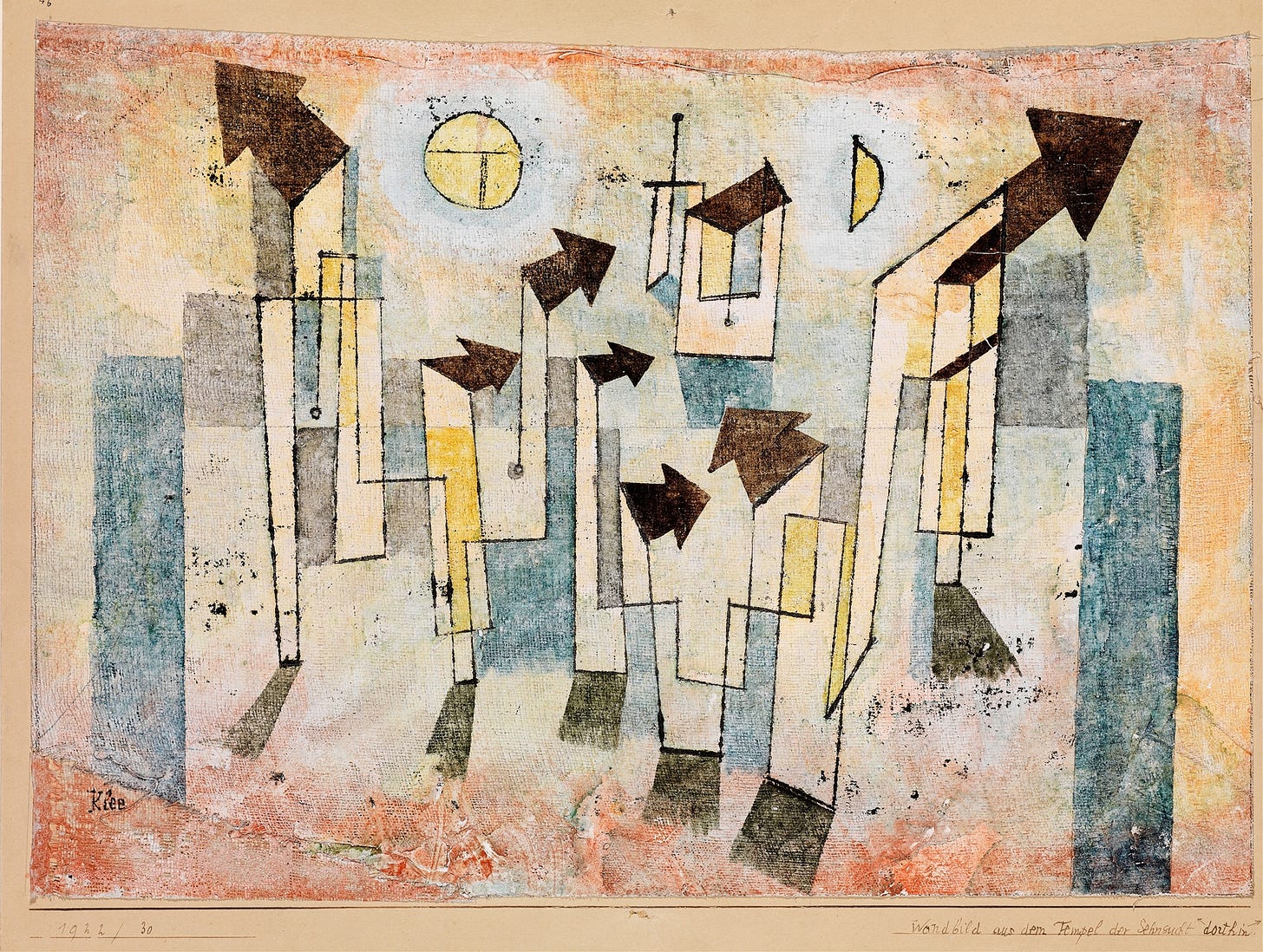

Where a big self was once frustrated by the bounds of the world’s options, a small self is now overwhelmed by those options’ oceanic expanse, in which desire is the only compass that might guide us. Wanting is what differentiates an otherwise canvas-like horizon of azure into arrows, into the trade routes and adventures one might take.

The second serious romantic relationship of my life was with a law student who studied cognitive science in college. I had dropped out of law school myself; I had been paralyzed and unable to work, unable to decide if I really wanted to be a lawyer, and I had also been ripped apart, not for the last time, by heartbreak. I was seeing a therapist and taking antidepressants. My new girlfriend said she knew what my problem was. There were two types of people in the world: satisficers and maximizers. Satisficers can pick from a menu of options right when they see something they want. Maximizers, on the other hand, scan the whole menu and then waste time and energy worrying about what would be the very best thing to pick. I was a maximizer, she said, and it led to all my trouble with self-doubt, indecision, and giving up on things I had been trying to do.

In some situations, maximizing isn’t so bad. If you’re picking from a menu at a restaurant, you’re comparing a pretty limited number of options, and you’re stuck sitting there anyway, so no big loss. But you might waste more time if you’re stuck picking restaurants from a menu of delivery options. My third serious romantic relationship was with a medical student who could never decide what to eat. “What do I want?”, she would ask me. I would run through all the cuisines we had around us. Sometimes one would stick out to her, but sometimes none of them would, or they all would. Personally, I feel this pressure the most in romance itself: in knowing that, as much as I liked yesterday’s date, I might have another tonight if I put in a good half-hour of swiping on a dating app. But maximizing in romance is infamously stupid. You get old, you get jaded; you end up without even the options you hadn’t been sure were good enough. You end up missing someone, or even multiple people, and not being able to remember why you got tired of them. The next, slightly-better option just doesn’t materialize. The kitchen is closed; the menu is blank.

But I don’t think maximizing is really the problem. The problem is with not wanting, or not knowing what one wants. In the contemporary world—or, again, the world at least that most readers probably live in—wanting is not an impediment to a happy life in a situation of scarcity but a necessary skill for a happy life in a position of plenty. The satisficer who doesn’t want, or doesn’t know what they want, is in just as bad a jam as the maximizer. You need to be able to encounter a button and press. You need to be able to encounter a face and swipe right.

Friends who date a lot often put people into “boxes” after a two-second glance at a dating-app profile: good for a chat over drinks, but nothing lasting; good for a friendship, but nothing physical; good for casual physicality, but nothing serious; good for a serious relationship. Everything in the world, including people, appears to them decked out with uses and functions, the way a ball might seem to be calling out to be kicked or a stick might seem to be calling out to be picked up and waved around. There’s a secondary lesson there: If you’re not good enough at wanting, someone else will do your wanting for you. Maybe this is what the much-ballyhooed “codependent relationship” really comes down to: a relationship in which it is only one person’s job to really want. Of course, this can arise because the other party simply isn’t quite sure how to want, how to desire.

Another way in which the restaurant scenario is not a good model for decision-making is that we usually aren’t presented with one single moment of high-stakes decision, but rather a steady stream of decisions whose stakes are unclear. Life is a set of waiters bringing us hors d’oeuvres, any of which might be delicious or poisonous. You might think that you’ve made a decision, but you have to make a hundred more to lock it in. I take a deep breath and order some new shirts; I take another deep breath and buy a bus ticket; then because I choose to put my luggage underneath the bus rather than carrying it on, I end up losing the shirts. Decisions, and situations more generally, are fragile in this way: There is little time to sit back and enjoy things as they are; you have to keep moving, keep reaffirming that what you have is what you want, still, in this next moment, to stay in one place.

The relationship between maximizing and not knowing what one wants is often the opposite of what my ex-girlfriend thought. On her estimation, I couldn’t get a feel for what I wanted because I was a maximizer: I suffered from the impulse to keep surveying all my options, to dwell in possibilities, trying to make the perfect choice. On my model, I was a maximizer because I couldn’t get a feel for what I wanted: I had to look at more and more options because nothing really stuck out in the way wanting tends to make things stick out. Balls weren’t there to be kicked, sticks weren’t there to be waved. Entrees weren’t there to be ordered. Everything was just there. Since the wanting itself never appeared, never attached itself to some object and gave it that special shimmer I was waiting to see, I ended up left with an even more paralyzing set of options.

But she was right in a way, too. Since I wasn’t up to wanting, I wasn’t up to living: to having a life, in the way lives can be had in the modern world. What I had, what I often still seem to myself to have, is like the tuning-up of a life, a timid back-row cello just waiting for that perfect C, G, D, and A to arrive before the bow can stroke the catgut of the world. The concert never begins; the only ear is the cellist’s, glued to the wood, listening for sounds that echo darkly only inside the instrument. That’s life if you can’t learn how to simply want.

Really great essay. I think where this dynamic really comes into play (at least in my case) is in the professional world. I have always been in awe of those people who always knew what they wanted to do and pursued it. A “calling.” Less about success in that chosen field, they always seem especially content because they are doing what they truly love. What if one doesn’t really know what one wants? It’s entirely possible to be productive, work hard, be professionally successful, be great at one’s job, and still never feel fulfilled. I think this is slightly different than the classic “paradox of choice”; it’s not about not being able to choose among all the options, but really about having no idea what you want to do.

What about maximicing: scanning the whole menu and choosing everything right away?