Welcome to CrowdSource, your weekly guided tour of the latest intellectual disputes, ideological disagreements and national debates that piqued our interest (or inflamed our passions). This week: What’s in a name?

Join us! CrowdSource features the best comments from The Crowd — our cherished readers and subscribers who, with their comments and emails, help make Wisdom of Crowds what it is.

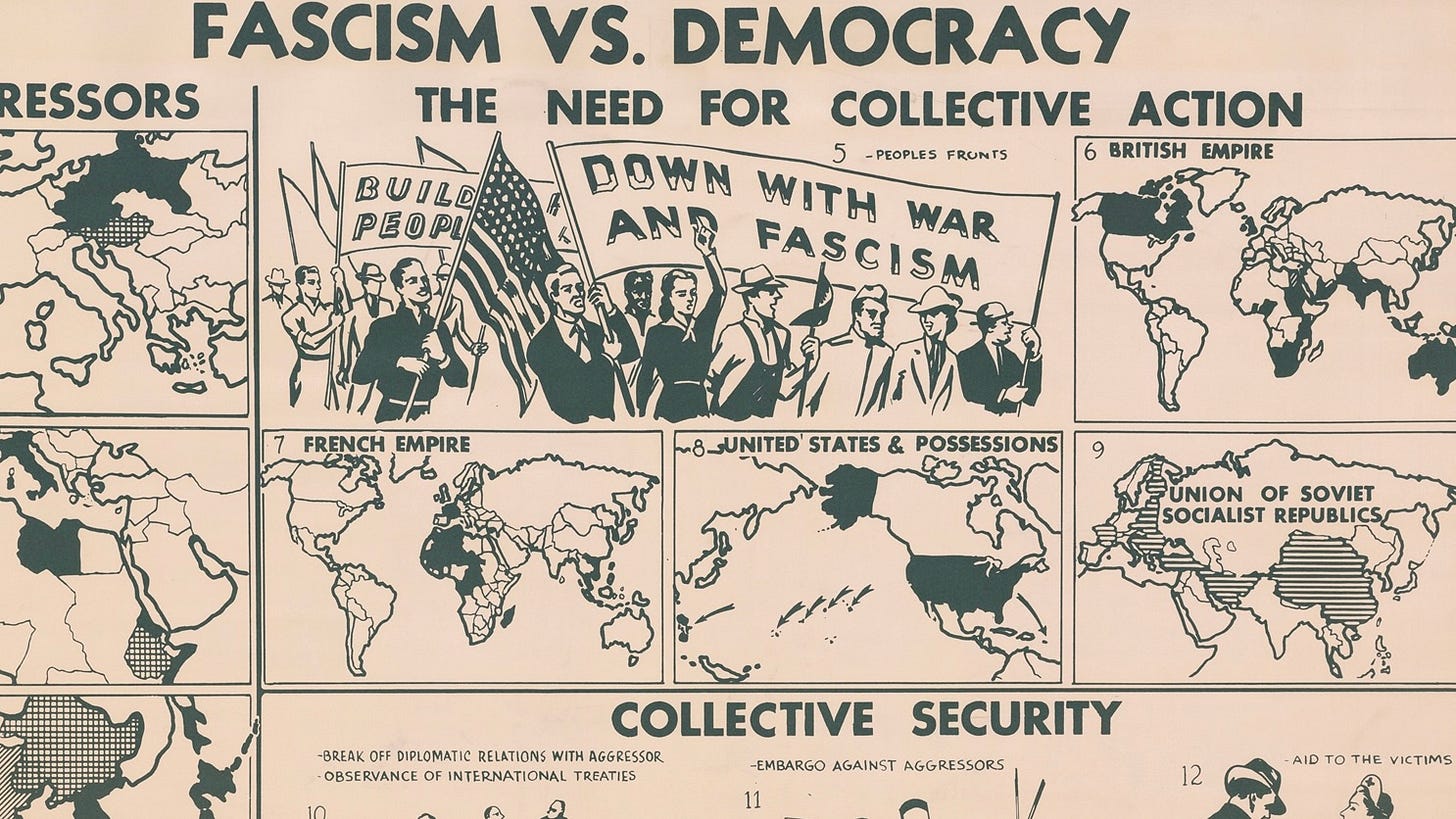

Is Donald Trump a Fascist?

Journalists and intellectuals have been debating this question since 2016.

The question came up again during Zohran Mamdani’s meeting with Trump last Friday. On Saturday, Mamdani affirmed that he still believes Trump is a fascist.

How goes the fascism debate?

The Fascism Debate

Some recent salvos.

Trump Is a Fascist. Along with historian Timothy Snyder (author of On Tyranny), the most famous intellectual calling Trump a fascist is Jason Stanley (who wrote How Fascism Works). Both Stanley and Snyder left Yale in 2025 to live under self-imposed exile in Canada. In an interview earlier this month, Stanley rehashed his views:

… we’re creating large concentration camps for immigrants. Lawyers can’t get into these places. Congress people are being blocked from their oversight role. So we now have concentration camps in the United States. We have people in masks kidnapping people off the streets.

Fascism is European; Trump’s Ideology is All-American. Daniel Bessner, in March:

There is a fundamental truth at the heart of Trumpism that makes comparisons to European fascism difficult to sustain. Put simply, Trump and his hangers-on are building on long-standing American traditions and are using the normal tools of the American government to dismantle democracy.

Trump Could Be An American Fascist. Fred Glass responds to Bessner:

In most places, and for anyone who knows much about World War II, the analog with Italy and Germany can be helpful in demonstrating parallels; that doesn’t mean we are reducing American fascism to the analogs.

Perhaps the better words for all this are the older terms “tyrant” and “tyranny.” Tyranny, since its first formal explication by Plato in The Republic, suggests fundamental disorder and irrationality. The totalitarian regime pursues a world of terrifying ideological consistency, destroying with ruthless logic anything that gets in its way — but the tyrant is arbitrary and incontinent, subject to unruly passions and appetites.

America Is Too Big For Fascism. So wrote (recent WoC guest) Ross Barkan right before Trump’s re-election:

The debate itself is wearying and bound to slowly turn your brain to soup. Instead of arguing to you that Trump is not a fascist, I will make a different proposition, one I feel much more certain about: the United States of Ameria is too big for fascism. Federalism itself is too unwieldy for fascism.

The State Is Too Large and Unwieldy for Fascism. So argued Tyler Cowen in 2018. In June, he revisited his argument:

I do not doubt … that the Trump administration represents a major increase in blatant corruption, and a deterioration of norms of governance, most of all in the areas of public health and science but not only. I think of America as evolving back to some of its 19th century norms, and often bad ones, not fascism.

We Need To Put the Debate to Rest. Last year, Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins edited a volume about the fascism debate: Did It Happen Here?: Perspectives on Fascism and America. In the book’s introduction, he writes:

… we should be suspicious of historians moonlighting as prophets of doom and democratic avengers. Their desire to sound the tocsin against the threat of recurrent heresy too often obfuscates, rather than clarifies, the complexity of current events. Being overfixated on the traumas of history can make it difficult to grasp what is new. It also leads to a never-ending blame game as to who is responsible for the collapse of the older order of things. The way forward is to put the fascism debate to rest, even as we try to come to terms with the neurosis it has revealed in us …

Did We Already Cross the Rubicon?

The detention, last March, of Columbia student and activist Mahmoud Khalil provoked two thinkers from the Trump-is-not-a-fascist camp to revisit their views. (Here’s something we published at the time about the Khalil affair.)

Trump Is Too Weak To Be A Fascist. Political theorist Corey Robin has held the same opinion throughout the Trump era: fascism is an ideology of strength; Trump, as well as the American political system as a whole, is fundamentally weak. As he wrote in 2021: “where liberals and leftists saw power on the Right, I saw, and continue to see, paralysis. Not just on the Right, in fact, but across the political spectrum.”

“Shaken Out of My Skepticism.” After the Khalil detention, Robin said in an interview:

I was skeptical coming into this second administration that they would be able to wield the kind of power that people feared they would wield. I have since turned out to be wrong. They have set off multiple conflagrations and I have been shaken out of my skepticism.

“Tyrannophobia.” After Trump’s victory in 2016, Yale Law professor (and friend of Wisdom of Crowds) Samuel Moyn wrote:

… tyrannophobia is blinding many to the real warnings of the election: A dysfunctional economy, not lurking tyranny, is what needs attention if recent electoral choices are to be explained — and voting patterns are to be changed in the future.

“A Big and Flagrant Step.” A few weeks after Khalil’s detention, Moyn posted:

The Point of This Debate. Also after the Khalil case, John Ganz reflected on the purpose of the fascism debate:

Analogies are always imperfect and need to be refined. I ultimately thought the fascism thesis was what the philosopher of science Imre Lakatos called a “progressive research programme”: that is to say, it could make certain strong interpretations and even predictions about what was going on and it had a fairly good track record in that regard.

American Literature Imagines Fascism

Two examples.

It Can’t Happen Here is Sinclair Lewis’ 1935 dystopian novel about a fascist dictatorship in America:

“Nonsense! Nonsense!” snorted Tasbrough. “That couldn’t happen here in America, not possibly! We’re a country of freemen.”

“The answer to that,” suggested Doremus Jessup, “if Mr. Falck will forgive me, is ‘the hell it can’t!’ Why, there’s no country in the world that can get more hysterical — yes, or more obsequious! — than America. Look how Huey Long became absolute monarch over Louisiana, and how the Right Honorable Mr. Senator Berzelius Windrip owns his State. Listen to Bishop Prang and Father Coughlin on the radio — divine oracles, to millions. Remember how casually most Americans have accepted Tammany grafting and Chicago gangs and the crookedness of so many of President Harding’s appointees? …”

“The Hell It Can’t,” Saul Bellow’s first published story (1936), was a variation on Lewis’ theme:

Sometimes he felt that he ought to say something to the men about his not being a coward. Maybe they’d admire his nerve and let him go. Tender mercy, “Go on, beat it then” or “Got one myself at home.” Or perhaps he could appeal to the houses, the walls, the trees themselves. They should know him. They would miraculously save him. Such things had happened. The rod budded out with almond blossoms. The men marched behind and before, their faces like slag: motionless. Henry said nothing.

From the Crowd

A couple of responses on last week’s CrowdSource, “What is Postliberalism?”:

Words, Words, Words. The University of Utah’s Hollis Robbins is not impressed:

I don’t know. Creating a category, naming it, and then seeing what fits in it seems to be why everyone is running in circles rather than building anything that lasts. An abundance of categories and subcategories will not promote human flourishing.

Further Classification. History and Bible buff Noah Smits nuances the “postliberal” label:

I wouldn’t consider Sohrab Ahmari postliberal since he still trusts institutions and generally speaking wants to conserve rather than accelerate. His critique of corporate power is more in line with the populist conservatism of Josh Hawley and Matt Taibbi. I’ve always perceived postliberal to treat liberalism as a step on the way to something else which we’re just now getting past. Nick Land seems quintessentially this. Seems like there is also a less intellectual movement, more vibes and culture, of “now that we’ve tried liberalism and gotten sick of it, let’s explore what’s next,” maybe best represented by Red Scare.

See you next week!

Wisdom of Crowds is a platform challenging premises and understanding first principles on politics and culture. Join us!

Did Lewis even use the word Fascism? My memory is he did not. I read ‘It Can’t Happen Here’ 16 years ago, commenting:

“A disturbing book that recognizes tendencies which are still embedded in the American psyche. Totalitarianism doesn't come from the right or left--it is a response to fear. Politicians, journalists, and individuals who exaggerate risks and encourage fear and divisiveness are the true enemy of democracy. The political and social message outweighs the [weak] prose.”

The primary message I took from the book was that under sufficient levels of stress, virtually everybody would support something similar to Nazism. If they feel sufficient fear, and that fear can be dramatically augmented by a demagogic leader exploiting mass media, then ordinary people will begin reporting their neighbors to the secret police. Written long before Arendt’s book, Lewis similarly recognizes the banality of the phenomenon, as the wholesale mistrust of family, friends, and neighbors leads to widespread support for cruelty.

The second message I took from Lewis was that political orientation is merely a convenience for a populist demagogue. He and his followers are enthralled with power and thrill seeking, and whether they hew more closely to the previous understanding of political left or right is moot.

The wisdom of Lewis approach is that he highlights the psychological, social, and political power dynamics of a demagogic populist movement while avoiding terminological and even political baggage. He provided a compelling argument that ‘it’ can happen here, and by extension, virtually everywhere, in large part by avoiding the distracting and contentious arguments over what exactly ‘it’ is. Humans have an unfortunate tendency towards ‘my side bias’, attributing positive motivations to their own group, and negative motivations towards other groups, but by maintaining some ambiguity about party orientation, and the social policy goals of the populist leader, Lewis’ book is less likely to trigger that inherent my side bias.

My position is that the terms ‘NAZI’ and ‘Fascist’ are inherently associated with a specific time and place, and that attempting to apply them today can be counterproductive. The “who’s a Nazi?” Game is a fools errand, denigrating into useless arguments over terminology. The critical thing to keep in mind instead is the degree to which a politician and movement are closed or open. The cohesion and excitement of a closed society needs to be recognized, along with the actionability benefits of such widespread synchronous political energy. But Authoritarianism always comes at a cost. Its proponents correctly recognize the myriad weaknesses of Liberal Democracy, while vainly believing that they can avoid the inevitable tragedy of all other political systems.

Lewis provides a very clear message about what the road to hell looks like in a modern democracy. It can happen anywhere

Huh? All I see here is the usual highbrow verbiage, and nothing even resembling a rational thought.

Let's hear what the local plumber thinks. Or an electrician. Let's here from farmers. How about rural folks in general? What are people saying in North Dakota? Not relevant, you say? Well, what is relevant about ivory tower progressives pontificating amongst themselves, as if anyone else is supposed to give a damn.

Here's the real problem that progressives have with Trump: He is the first significant political figure to point pout how irrelevant the ivory tower left really is. They are nowhere near as smart and perceptive as they tell each other. And they are entirely useless, worse than useless, to the rest of America. If any of that makes Trump a fascist, a tyrant or a dictator, well, bring it on.